Why Curfews Were Unconstitutional for Non-Citizens of Australia

So....what about lockdowns for Australian citizens then?

During the pandemic in Australia, both lockdowns and curfews were implemented as “public health” measures to limit movement to reduce the transmission of the SARS CoV-2 virus and COVID-19 disease.

Both measures restricted individual freedoms, often enforced through police patrols, fines, and penalties for non-compliance. The NSW Police Commissioner at the time even suggested treating the virus like a criminal to reduce community transmission:

Restrictions were justified on the basis of public safety, with governments arguing that restricting movement - whether for entire days (lockdowns) or during specific hours (curfews) - was necessary to prevent outbreaks. Both measures were frequently extended beyond their initial timeframes, often without clear evidence of effectiveness, leading to growing public resistance and legal challenges.

Yet, on reflection, lockdown was by far the worst of the two restrictive measures. Lockdowns confined people to their homes for months, eliminating public life during all hours, leading to economic devastation, mental health crises, and social isolation. Essential activities such as work, schooling, and even outdoor exercise were heavily restricted or banned altogether in some cases. The prolonged nature of lockdowns caused widespread financial hardship, while curfews, though restrictive, still allowed some level of daytime normality.

More importantly, whilst most Australians were able to partake in “Freedom Day” in late 2021, lockdowns which extended exclusively for the “unvaccinated” were clearly punitive. Unlike broad lockdowns, which affected everyone, these extended restrictions for the “unvaccinated” functioned as a form of coercion, limiting their ability to work, travel, and engage in public life unless they complied with “vaccination” mandates. The measures were framed as protecting public health, yet they lacked clear scientific justification, particularly once it became evident that “vaccination” did not prevent transmission (not that it was ever even indicated for doing so).

On reflection, as bad as all “public health” interventions were during the pandemic, curfews were preferable to lockdowns because they were less restrictive and did not specifically target or marginalise a cohort of the population like the “unvaccinated”.

But, in a significant decision in late 2024, the High Court of Australia held that even curfews were unconstitutional because they were punitive and that punishing things was the prerogative of the Judiciary; not the Executive. The Court emphasised that restrictions for “non-citizens” of Australia, including adhering to nightly curfews and wearing ankle bracelet monitors, could not be justified as administrative necessities and were, in effect, forms of punishment.

The High Court delivered a majority judgement, with two dissenting opinions; from the Honourable Justices Robert Beech-Jones and Simon Steward. This was the same Beech-Jones who, only a year prior, was appointed to the High Court. The same Beech-Jones who, in 2021, adjudicated in the NSW Supreme Court on a pivotal case challenging the legality of NSW’s “COVID-19 vaccine” mandates. In the mandates case, Beech-Jones ruled the health orders mandating “vaccination” were lawful under the Public Health Act 2010 and did not constitute coercion; rather, just a “movement restriction” that impacted one’s ability to move or work.

Just a mere inconvenience really.

Remember, no one ever forced you to be “vaccinated”.

Background to the High Court decision

On 28 November 2023, the High Court of Australia ruled in NZYQ v Minister for Immigration that the indefinite detention of non-citizens without a real prospect of removal from Australia was unconstitutional. The Court found that such detention served a punitive purpose, which is beyond the Executive’s power and infringed upon the Judiciary's exclusive role in imposing punishment.

Following this unfavourable ruling, the Federal Government introduced emergency measures requiring detainees who might be released to wear ankle bracelets and adhere to mandatory curfews “to keep the community safe” and to “strengthen relevant migration laws”.1

These “emergency measures” were rushed through both Houses of Federal Parliament with the debates and votes being conducted on the same day, with near unanimous support resulting in this Bill becoming legislation the same day.

From experience, we know that the State likes to keep the community safe, whether from respiratory pathogens, misinformation, disinformation, social media or racists, and therefore, on this occasion, the threat to community safety from “non-citizens with a history of serious criminal offending, including but not limited to serious offences committed in Australia” was at least consistent with its perceived mandate to intervene in our daily lives for our “safety”.2

The NZYQ v Minister for Immigration decision resulted in the release of approximately 150 detainees, with the Government warning at the time a “significant number” had been convicted of “serious criminal offences”.3 It was later clarified that approximately half of these detainees had been convicted for serious crimes such as murder, attempted murder, armed robbery, violent assault and sexually-based offending, including against children.4 By June 2024, approximately 85 of 160 of the detainees released were required to wear ankle bracelets, 77 of which also had curfews between 10:00 pm and 6:00 am.

Some of those released continued to reoffend. Though many were for the offences of non-compliance with the monitoring restrictions, some were charged for serious crimes such as murder, assault, trespass and for child safety concerns. Yet, for those cases presenting to the courts for the breaches of curfew or reporting obligations, the Judiciary tended to side with the defendants. For example, Abdelmoez Mohamed Elawad, a 45 year-old Sudanese man who had racked up more than 200 criminal charges within a 12-year period in Australia, was bailed in the Supreme Court of Victoria by Justice Michael Croucher for the single charge of not complying with his curfew restrictions:

“Justice Croucher said while it was appropriate for the prosecution to point to his background, “the question is whether he should be released on bail on this charge, this single charge, the circumstances of which are (he’s) found in Footscray beyond his curfew time.”

“Is that it?” the judge asked.5

In a similar case in May 2024, Burundi man Kimbengere Gosoge had six charges laid against him for breaches of curfew and failing to maintain his monitoring device. Despite having been convicted for trespass, possession of amphetamines and stealing since his release from immigration detention only six months prior, he was handed a one-year suspended jail sentence.6

The legal basis for these punitive measures was tenuous and the Judiciary had demonstrated a lack of appetite to sentence offenders who breached these monitoring and movement restrictions.

By August 2024, the “draconian” and “punitive” approach taken by the Federal Government in managing community safety was challenged by one known by the pseudonym “YBFZ” in Australia’s High Court. In the statement of claim, the plaintiff YBFZ argued punitive measures such as wearing ankle bracelets or being subject to curfews could only be imposed by a court following a criminal conviction, not administratively by the government. This, he contended, violated the separation of powers required under Chapter III of the Australian Constitution, which reserves the imposition of punishment to the Judiciary.

In its submissions in defence, the Commonwealth Government suggested that such curfews were not punitive, but were in fact routinely employed in Australia:

“[C]onsiderably more onerous curfews are imposed for purposes that obviously are not punitive. For example, curfews were imposed by public health officials in Victoria and certain regions of New South Wales during the COVID-19 pandemic (and, likewise, in regions of the United States and Canada.”7

The Commonwealth’s argument was striking for what it inadvertently revealed. By citing pandemic lockdowns as “considerably more onerous” measures that were supposedly non-punitive, it acknowledged the reality of the true nature of lockdowns. After all, how was it that the Commonwealth, wielding significant constitutional power over the States and Territories and during a supposed national crisis, allowed such extreme incursions on liberty to be imposed unchecked?

In its judgement, handed down on 6 November 2024, Justices Gageler, Gordon, Gleeson, and Jagot upheld that “nightly curfews and ankle bracelets are forms of punishment which have real impacts on people’s lives and cannot be justified”.

Fundamental protections in law against arbitrary detention and interference with bodily integrity apply equally to all people in Australia, whether they are citizens or not.

Just not during a period of a State-declared “emergency” for Australian citizens it would seem.

We all had equal rights to liberty and bodily integrity, but the rights of criminal non-citizens of Australia were more equal.

Summary of the majority judgement and concurring opinion

The following summary paraphrases and/or quotes the Justice’s majority judgement.

The law of the country gives value to bodily integrity and liberty from “arbitrary” interference.8 Under the common law, every person’s body is “inviolate” and “each person has a unique dignity which the law respects and which it will protect”.9 Both the curfew and monitoring condition infringed on these inalienable rights of the individual.

Furthermore, the language of the Migration Amendment (Bridging Visa Conditions) Act (The Act) that imposed curfews and monitoring conditions was too broad and, therefore, infringed on the exclusively Judicial power of the Commonwealth.10

Curfews

The curfew imposed on the plaintiff was neither trivial nor transient in nature. For nearly one-third of the day, he was confined to his specified place at his notified address. The plaintiff had to be sufficiently organised by 12:00 pm the previous day if he wanted to change his notified address and he was constrained if he wanted to travel further in the community to be able to return to his notified address by the time the curfew commenced each night.11 These conditions were punitive because they amounted to a “deprivation of liberty”which was “relatively long-term”.12

In some respects, the curfew condition should more correctly have been called “home detention” because a curfew only prevents movement after nightfall, whereas the plaintiff could be held at a specific place for a period that could include daytime.13

Contrary to the defendant’s submissions, “other types of curfews (for example, to prevent infectious diseases spreading or to restore public order) do not assist. Curfews may be of many different kinds and for many different purposes and, by reason thereof, will have different constitutional significance.”14

For these reasons, the curfews were considered unconstitutional.

The monitoring condition

The fitting of the ankle bracelet involved what would otherwise be the commission of “trespass to the person (in the forms of assault and battery). The monitoring device then continued to be in contact with the wearer thereafter, as a direct and immediate continuing consequence of what would otherwise be the tort of trespass.”15 It was chunky and not discreet and everyone who saw one wearing it would immediately recognise it and assume the wearer presented some form of risk. Its continued presence on the body could not be described as a slight or modest interference with bodily integrity.16

The ankle bracelet had to be charged twice per day and it took 90 minutes to be fully charged and the plaintiff would face imprisonment if it was not charged or properly cared for and maintained.17 The charging device also had to be charged to ensure that it could charge the ankle bracelet. The practical effect of this restriction was that the plaintiff had to be somewhere near a mains power supply virtually at all times, a further deprivation to his liberty.18

Furthermore, the continuous monitoring of the plaintiff would breach his privacy and would divulge to the complete stranger monitoring his location, the places he visited which might reveal his political, religious, sexual and other personal affiliations.

The endless monitoring created real physical, psychological and emotional burdens for the plaintiff which made them punitive, and therefore, unconstitutional and invalid.

The dissenting opinions

Beech-Jones

Chapter III of the Constitution and NZYQ

Not every form of hardship or detriment imposed by the Executive constitutes punishment. Therefore, the Constitution was not infringed simply because Commonwealth legislation authorised the Executive to interfere with common law rights.19

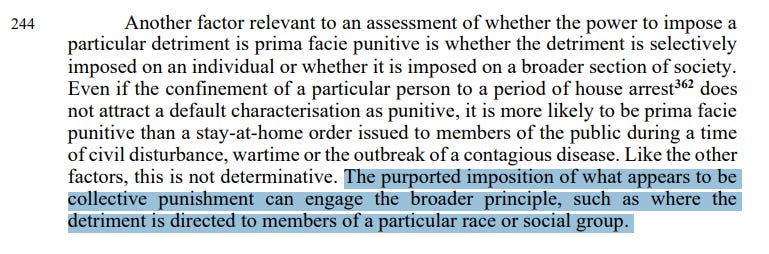

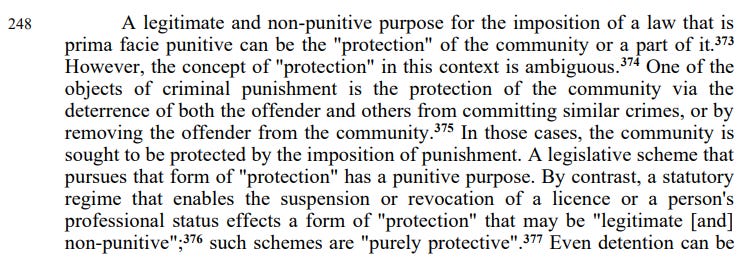

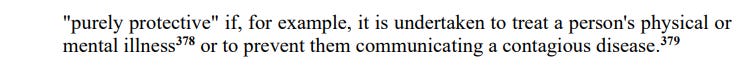

A relevant test of whether a restriction is punitive is whether it is selectively imposed on an individual or whether it is imposed on a broader section of society. Even if the imposition of house arrest to a particular person was not deemed punitive, it would be far more punitive than a “stay-at-home” order issued to the public during wartime, a civil disturbance or the outbreak of a contagious disease. The measures, after all, were not collective punishment targeted at a particular race or social group.20 Detention should be considered “purely protective” (not punitive) if it was undertaken to prevent them from communicating a contagious disease.21

A law might provide for the detention of persons affected by an infectious and serious disease, but the legislative scheme for that detention might extend the detention well beyond the period during which the individual is infectious. Such detention would be greater than what the reasonable protection of the public requires. In that case, the power of detention could not be seen as necessary to achieve the legitimate and non-punitive purpose of preventing the spread of a deadly disease and, therefore, it may be inferred that the purpose of the detention is punitive. Leaving aside the duration of the detention, the fact that there may be other less draconian means of addressing the spread of such as disease would be relevant to the extent that it enabled us to assess the true intent of the law - be it protective or punitive.22

But, these measures were only ever intended as preventative and regulatory, not punitive. Whilst the threat of punishment existed, that would have been a separate process if or when the law was broken. The Act was “purely protective” because it was designed to make the visa holder comply with these conditions, not to punish them by imposing the conditions.23

The power to impose the monitoring condition

There is no historical or other basis for treating interferences with privacy as punitive and there are numerous examples to the contrary. The mere collection of information about a visa holder’s movements into, out of, or within the country are purely protective. Examples of interference with bodily integrity abound which would not be characterised as punitive; submitting to decontamination or medical testing, the use of force in executing a warrant and making an arrest and the taking of fingerprints, an iris scan or physical measurement, non-consensual body searches at airports. Perhaps these all have a shorter duration, but they are examples of far more intrusive interferences with bodily integrity than this discreet, light and small monitoring device some visa holders had to wear.24

Any stigma that the plaintiff experienced because of wearing the discreet device could be avoided by using a smaller monitoring device like a smart watch, or clothes that would easily cover the device. In any event, the stigma associated with wearing the device was only incidental to the purpose of the device. The purpose of the law matters: it was to monitor compliance; not to shame.25 If, however, “the use of a public symbol to mark out the members of a particular race or members of a social group for disapprobation is a form of stigmatisation [then] that could amount to collective punishment of the kind adverted to earlier which would warrant the characterisation of any law authorising its application as punitive”.26 [emphasis added]

The power to impose the curfew condition

The plaintiff made the inaccurate statement that during the period in which the curfew condition is in effect, the Commonwealth has “total control over his liberty”. Nothing like “total control” existed, particularly in comparison with those of the NZYQ cohort who were in immigration detention. The plaintiff’s statement was inaccurate because the deprivation of his liberty was comparatively low: he could freely choose his place of residence anywhere in Australia; he could change these at short notice, he could supply a number of different addresses and choose to stay at any of them with notice. The Commonwealth did not dictate what occurred at those premises, who could reside or enter them, or did not reserve any power to enter those premises.27

“The restriction on liberty and movement for a third of the day, supported by the threat of criminal prosecution and mandatory imprisonment, is a very significant restraint. The Commonwealth sought to resist this conclusion by pointing to the type of curfews noted above, namely those applicable in times of civil unrest, wartime or during a pandemic. However, those are examples of general curfews. Here, the curfew condition is specifically directed to a particular individual based on an assessment that must include a consideration of the risk they pose and most likely includes a consideration of their past behaviour.”28 [emphasis added]

Here, in the case of our visa holders, “specifically directed” curfews to “particular individual[s]” were based on an assessment of their risk they posed.

In sum, the curfew condition is not as severe as the plaintiff contends, and therefore, is not punitive.

Discussion

The assurance in the majority judgement that the common law treats the human body as “inviolate” and respects liberty and bodily integrity, raises an important question about how these principles were abandoned during the pandemic.

Several unprecedented interventions affecting liberty, bodily integrity, autonomy, and privacy in ways that had not been seen before were imposed:

Coercion from “vaccination” mandates violating informed consent;

Lockdowns;

Mandatory PCR-testing;

Quarantine;

Facemasks; and,

Even having to wear ankle bracelets in COVID-19 quarantine facilities.

To any reasonable mind, the curfew conditions were far less restrictive than lockdowns. On this test alone, if the curfew could be considered a “deprivation of liberty”, by the same reasoning, the lockdowns must have been too.

Similarly, the interferences with bodily integrity (as noted above) were far more invasive and extensive than the ankle monitoring condition imposed on the visa holders. On this test too, if the wearing of the ankle bracelet was an interference with bodily integrity tantamount to assault and battery, then any of the above would exceed this test and must also be considered so too.

But this discussion only compares the broad lockdowns experienced by all during the pandemic.

The lockdown which was extended for the “unvaccinated” - that particular “social group” to which Beech-Jones repeatedly referred in his dissenting opinion - warrants closer analysis.

Another esoteric reading of Beech-Jones’s opinion

Beech-Jones supplied several interesting hypotheticals in his reasoning which suggest that pandemic measures which specifically targeted a “social group” were unconstitutional.

In other words, when a restriction focused on a particular social group, such as the “unvaccinated”, it would be an example of a collective punishment and could be considered punitive rather than protective, therefore, invalidating it.

As the “vaccines” were never indicated for the prevention of infection and the transmission of COVID-19 disease, and the real-world observational evidence proved this to be true, the extended lockdowns for the “unvaccinated” were never “purely protective” because anyone “vaccinated” or “unvaccinated” could still contract and transmit COVID-19. Once again, the continued lockdowns for the “unvaccinated” could not have been “purely protective” for the community and must, therefore, have been punitive.

In the event that we accepted that lockdowns were even valid for the “purely protective” purpose of mitigating the spread of an infectious and serious disease, the extension of detention well-beyond the period in which the individual was infectious would be “greater than what the reasonable protection of the public requires”, meaning the measure would be punitive, and therefore, invalid.

But there is an even more important aspect to Beech-Jones’s hypothetical here.

The extension of lockdowns for the “unvaccinated” had nothing to do with whether or not one was infectious. Extending the deprivation of the liberty of otherwise healthy people, simply for refusing to subject themselves to “vaccination”, was plainly and simply punitive.

On consideration that there were several less draconian methods of addressing the spread of such a disease, the measures taken by the State to extend the restrictions against a particular social group revealed that the true purpose of the law was to authorise “the infliction of punishment” on the “unvaccinated”.

In many examples, the “unvaccinated” were required to wear or display a “public symbol”, like a face mask or “vaccine passport”, once the broad lockdown restrictions had been removed for the “fully vaccinated” cohort of the population.29 By Beech-Jones’s reasoning, this stigmatisation could be regarded as collective punishment of the “unvaccinated”, again, rendering these measures invalid.

Our lasting question with Beech-Jones again is, were these hypotheticals pivotal to his reasoning about the validity of curfews and monitoring conditions for visa holders in Australia?

Could Beech-Jones have, once again, been warning against the “slippery-slope” of measures which target particular social groups?

Conclusion

Incredibly, the majority judgement of the High Court of Australia in YFBZ v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs held that even serious offenders who had a violent criminal past, before and after arriving in Australia, had superior rights to yours.

Curfews, which, to any reasonable mind, were far less restrictive than lockdowns for Australian citizens, constituted a “deprivation of liberty” to these non-citizens.

Ankle bracelets, which were characterised as “assault and battery” on these non-citizens interfered with bodily integrity.

But, rest assured, under the common law, every person’s body is “inviolate” and “each person has a unique dignity which the law respects and which it will protect”.

Yet, for a shameful period in our history, these rights to liberty and bodily integrity only extended to those Australian citizens who:

Willingly enrolled themselves in the world’s largest clinical trial;

Had bought into the propaganda about prosocial behaviour;

Were virtue-signalling;

Had uncritically consumed the propaganda and were fearful for their health and safety; and,

Regrettably, could not resist the coercion to take the “vaccine” through mandates or otherwise.

If you were not in one of the above categories, then you were likely one of the “unvaccinated” (and presumably still are).

For you, these rights were suspended “for the greater good”.

Because “public health”.

Because “emergency”.

Of course, courts defer to “public health authorities” and “expert consensus” in controversial cases involving health emergencies, particularly when governments declare an “emergency” and invoke “emergency powers”.

But, as the pandemic has taught us, consensus - particularly “expert consensus” - should be interrogated, critiqued and challenged at all occasions - even if the Judiciary lacks the appetite.

A key aspect of Beech-Jones’s judgement in the pivotal “vaccine” mandate challenge was the assumption, widely held at the time, that COVID-19 “vaccines” significantly reduced both infection and transmission. This scientific premise underpinned the justification for mandates, particularly in workplaces and high-risk settings, under the reasoning that the measures served a public health purpose beyond “individual protection” (which we must now necessarily put in scare quotes too).

Had it been established at the time that COVID-19 “vaccines” did not prevent infection or transmission, the legal and evidentiary foundation for the mandates would have been significantly weakened.

Not that we didn’t know at the time.

The evidence was presented in the Kassam & Ors v Hazzard & Anor case, but, Beech-Jones effectively trusted one side’s version of “Science” while treating opposing evidence, no matter how well-founded, as inadmissible, irrelevant, or not as “expert” to the core scientific issues relevant to the case.

Is it any wonder that the State won?

We were presented with an alleged universal and authoritative consensus of belief about an unprecedented deadly disease because of State-directed censorship, clouded by the fog of State-crafted propaganda.

The disease, as it turns out, was less deadly before the global population was “vaccinated”.

How could any of that make sense?

In sum, it does not.

In the slightest of positive news from this experience, we know that the High Court will actively recognise the rights of the individual.

At least in certain, non-controversial or non-emergency circumstances.

Furthermore, we might have been subtly provided with an example of how to challenge any future incursions into our bodily integrity or liberty.

Perhaps the Paradigm has shifted.

Australian Government, “Explanatory Memorandum: Migration Amendment (Bridging Visa Conditions) Bill 2023”, Parliament of Australia, 2023, https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/legislation/ems/r7114_ems_78ddce5e-0329-4111-958d-7da135dd3666/upload_pdf/JC011495.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf, p. 2.

Ibid.

The Sydney Morning Herald, “Released Detainees to Wear Ankle Bracelets Indefinitely, as Lawyers Condemn ‘Disproportionate’ Response”, https://www.smh.com.au/national/released-detainees-to-be-fitted-with-ankle-bracelets-from-today-20231118-p5ekyv.html, accessed 31 January 2025.

ABC News Australia, “Half of 149 Released Immigration Detainees Convicted of Violent Offending, Kidnapping or Robbery”, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-02-12/half-released-immigration-detainees-convicted-violent-offending/103455458, accessed 31 January 2025.

The Australian, “Violent Serial Offender Freed on Bail by Victorian Supreme Court”, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/politics/freed-detention-detainee-had-breached-bail-22-times-given-another-chance/news-story/32fb5277b3633df36389a57415db9d6a, accessed 31 January 2025.

The Australian, “Murder, Curfew Breaches: Detainees Kimbengere Gosoge, Emmanuel Saki Allowed to Walk Free”, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/lawyer-urges-leniency-for-detainee-kimbengere-gosoge-due-to-punitive-curfew-conditions/news-story/5d5624d5162bd6edb634e87c98d582b1, accessed 31 January 2025.

YFBZ v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs, High Court of Australia, 2024, High Court of Australia, paragraph 12.

YFBZ v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs, High Court of Australia, 2024, Defendant's Submissions, High Court of Australia, paragraph 43.

Ibid., paragraph 15.

Ibid., paragraph 83.

Ibid., paragraph 51.

Ibid., paragraph 52.

Ibid., paragraph 104.

Ibid., paragraph 55.

Ibid., paragraph 57.

Ibid., paragraph 58.

Ibid., paragraph 59.

Ibid., paragraphs 60-61.

Ibid., paragraph 240.

Ibid., paragraph 244.

Ibid., paragraph 248.

Ibid., paragraph 253.

Ibid., paragraphs 284-286.

Ibid., paragraphs 299 and 306.

Ibid., paragraphs 308-309.

Ibid., paragraph 307.

Ibid., paragraph 316.

Ibid., paragraph 317.

Consider the following as just a few examples of punitive restrictions which persisted for the “unvaccinated” without a sound scientific or legal basis:

Queensland’s “Public Health and Social Measures linked to vaccination status Direction” here https://www.health.qld.gov.au/system-governance/legislation/cho-public-health-directions-under-expanded-public-health-act-powers/revoked/public-health-and-social-measures-linked-to-vaccination-status-direction

Northern Territory’s strict entry requirements for “unvaccinated” people here https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8653309

“Inwards Travel Restrictions Operation Directive” allowing only the “fully vaccinated” to enter Australia, which was rescinded only by the end of April 2022 https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/foi/files/2022/fa-220600418-document-released.PDF

Very interesting. I shall need to read this a couple of more times to get my head around it. Just to make the point that there is no covid-19, the alleged covid pandemic is a psyop from start to finish and the monumental effort on all the legal stuff being based on the premise that there is a covid-19 is essentially hot air from the getgo. It's all so utterly ridiculous. What a pantomime.