What happened with COVID-19 in NSW in 2022? (Part 3)

The NSW Ombudsman has decided to accept our Voluntary Public Interest Disclosure alleging "serious wrongdoing" by NSW Health and has escalated it to its Legal branch for investigation.

In the first of our “What happened with COVID-19 in NSW in 2022?” articles, we highlighted the many significant problems of the data published in NSW Health’s “Weekly Surveillance Reports” (The Weekly Reports) in 2022:

We brought these issues to NSW Health’s attention when this article was published, but did not receive a response. When we escalated this to the NSW Ombudsman, our complaint was dismissed as a “policy disagreement” that would not be pursued.

However, as we wrote in our open letter to the NSW Ombudsman in Part 2 of this series of articles:

The issues raised were not simply a “policy disagreement(s)”, but evidence of “serious wrongdoing” under the Public Disclosures Act (2022) due to NSW Health’s erasure of the data that was used to produce The Weekly Reports.

Following this request for review by the NSW Ombudsman, we received this unexpectedly positive news via email:

“Dear REDACTED

Thank you for your email of 9 May 2024.

Your request for your matter to be review [sic] under the Public Interest Disclosures Act (2022) has been accepted and is currently with our Legal branch. They will conduct the review.

We will be in contact with an outcome after the review has been completed.

Kind regards

REDACTED”

What’s this about again?

To reorient the reader.

Individuals can make a “Voluntary Public Interest Disclosure” (PID) if they allege “serious wrongdoing” under the Public Interest Disclosures Act (2022) (The Act).

“Serious wrongdoing”, as defined by The Act, can be one or more of the following:

The “serious wrongdoing” we alleged in our PID was “a government information contravention”, which, as defined in the Act, includes one or more of the following:

The State Records Act (1998) (The SRA Act) prohibits the disposal of (“by destruction or by any other means”) by a “person” (“includes a public office and a body [whether or not incorporated”]) of a “record” (“any document or other source of information compiled, recorded or stored in written form or on film, or by electronic process, or in any other manner or by any other means):

Indeed, the purpose of The SRA Act is, among other things, the protection of State Records and to ensure the provision of public access to such records:

“An Act to make provision for the creation, management and protection of the records of public offices of the State and to provide for public access to those records, to establish the State Archives and Records Authority; and for other purposes.”1 [emphasis added]

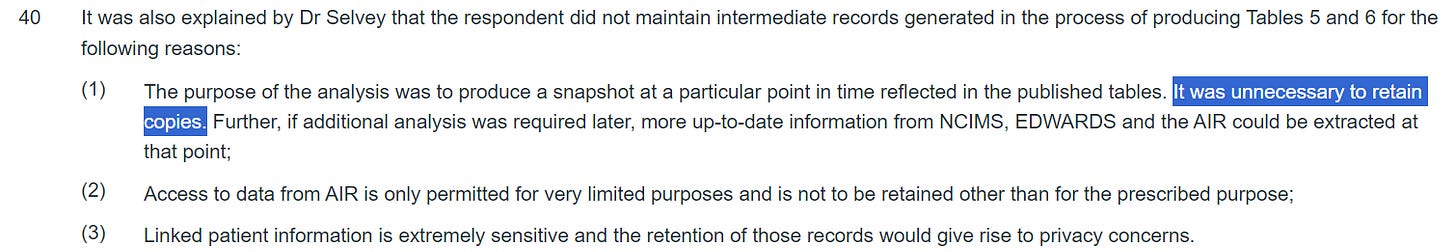

But these obligations were not met when the data used to produce The Weekly Reports was “erased” by NSW Health, citing, among other things, “privacy concerns” and, believe it or not, the assertion that it was “unnecessary to retain copies”:

In the above excerpt from the Ooi v NSW Ministry of Health (2023) judgement, NSW Health argued the duration and complexity of the efforts to produce aspects of the Weekly Reports (the “clinical severity by vaccination status” tables) meant that “records” existed only temporarily until “the required outputs [were] produced”.

By implication, the records had been disposed of because they existed only in machine Random Access Memory (RAM) temporarily:

But, even if the production of the Weekly Reports was complex and laborious, and the records existed only temporarily, the NSW Health defence is inadequate and demonstrates their non-compliance with The SRA Act.

Section 14.1 requires a “person” to not dispose of “record(s)” in cases where a “record(s)” which can only be produced “by means of the use of particular equipment or information technology (such as computer software)” [emphasis added]:

And so, the complexity or time-consuming nature of the production of the Weekly Reports is an irrelevant consideration to NSW Health’s obligations under The SRA Act. NSW Health are obligated to “take such action . . . to ensure that the information remains able to be produced or made available”.

We know, from NSW Health’s own admission, the data is unable “to be produced or made available” and it has, therefore, not been preserved. These data are considered “state records” under the State Records Act (1998), so their disposal constitutes “serious wrongdoing” under The Act.

So where to from here?

We know from Ooi v NSW Ministry of Health (2023), that the data used to produce the significantly flawed Weekly Surveillance Reports came from three sources, and therefore, should still be retrievable:

So it is possible the data used to produce the Weekly Reports can be recovered in order for NSW Health to clarify, correct and explain the anomalies and flaws in these reports.

Whether the NSW Ombudsman Legal branch views these as “serious wrongdoing” under The Act remains to be seen.

If they decline our PID, it will hypothetically only be for one of the three following reasons.

Reason # 1:

“It turns out the records weren’t erased after all!”

The NSW Ombudsman Legal branch will deny the strong evidence of “serious wrongdoing” by asserting the records were not actually erased by NSW Health and can be called upon once more by extracting and linking data from three separate sources (NCIMS, AIR and the Patient Flow Portal).

Reason # 2:

“Sure, NSW Health erased the data, but it wasn’t their data to begin with, so they have no obligation or right to keep it”

The NSW Ombudsman Legal branch will deny the strong evidence of “serious wrongdoing” by acknowledging the erasure of the data, but justifying this action because NSW Health were not the custodians of all of the data used to the produce the Weekly Reports (even if the NCIMS and the Patient Flow Portal are databases which are both maintained by NSW Health - but the AIR is not).

Reason # 3:

“Sure, the data was erased, but it’s not really serious wrongdoing is it?”

The NSW Ombudsman Legal branch will deny the strong evidence of “serious wrongdoing” by denying NSW Health’s actions had reached that threshold to be so considered.

If we are correct in predicting one of these three outcomes, then we will know the following:

If Reason # 1 - the data can be reproduced and NSW Health can correct, clarify and/or explain the anomalies in their Weekly Reports from 2022.

If Reasons # 2 or # 3 - the data cannot be reproduced and NSW Health will have to clarify and explain the anomalies in their Weekly Reports from 2022 and provide assurances that such errors will not be repeated in our next “pandemic”.

Conclusion

Our investigation into the Weekly Reports highlights significant concerns over data handling and transparency by NSW Health. These reports, which significantly influenced NSW’s COVID-19 policy responses, were based on data that now appears unreliable and possibly manipulated. This misrepresentation plausibly influenced public perception and policy regarding the severity of cases by vaccination status.

The legal review by the NSW Ombudsman's office, triggered by our inquiries, could provide action against NSW Health for their alleged “serious wrongdoing” under The Act. This determination will set a precedent for accountability and transparency in public health data management during crisis situations, and for the impending “Disease X” or “Bird Flu” pandemic: when, not if it arrives.

Ultimately, if the underlying data were as definitive as claimed in supporting the effectiveness and safety of interventions, there would be no justification for its concealment. The only plausible reason for restricting access to such critical data likely points to continuing the disinformation of the public narrative about the effectiveness of pandemic management strategies and the role of COVID-19 “vaccinations”, including their risk-benefit evaluation.

The suppression of data suggests an attempt to censor the full story, indicating that the official data might tell a very different tale about vaccine effectiveness and the appropriateness of the government’s pandemic policies.

And once again, only the truth gets censored.

State Records Act 1998 (NSW) No 17, Long Title.

Keep going!