What happened with COVID-19 in NSW in 2022? (Part 2)

The (non) NSW Health response, our complaint with the Ombudsman, a Public Interest Disclosure, our open letter, and now.................................................we wait.

In February 2024, we wrote the article (see below) exploring the concerning disrepancies between the COVID-19 data reported in NSW Health’s “Weekly Surveillance Reports” and those reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in its “Causes of Death” (2022) report.

What happened with COVID-19 in NSW in 2022?

The highlight of our article (and definitive lowlight for NSW Health) was the revelation of discrepancies in NSW Health’s death counts, misclassification issues, and inconsistencies in COVID-19 data reporting. The most concerning of these were:

The 2000+ extra COVID-19 deaths reported in the NSW Health Weekly Surveillance Reports in 2022, compared with the total reported by the ABS for the same period;

The six instances where the weekly “COVID-19 deaths” reported in NSW surpassed the total weekly COVID-19 deaths reported nationally for the same periods; and,

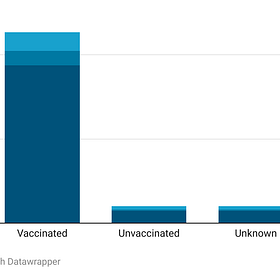

The arbitrary categorisation of the “unvaccinated” designed to make their outcomes according to infection, hospitalisation, serious illness leading to Intensive Care Unit admission (ICU) and death much worse (the “miscategorisation bias”).

Once we published our article, we sought comment from NSW Health.

We did not receive a reply (see the pattern here?).

So, we sought the intercession of the NSW Ombudsman, who, among other things, deals with complaints relating to:

“failure to reply to correspondence”; and,

“failure to act on complaints”.

We also made a “Public Interest Disclosure” to the NSW Ombudsman in this same complaint, alleging NSW Health had committed a:

“government information contravention”.

because, as it turned out, the information used to produce the dodgy NSW Health Weekly Surveillance Reports from 2022, had been erased.

Under the Public Disclosures Act (2022) (The PID Act), “government information contravention” can include “systemic issues with an agency’s record-keeping system that means information is not being stored appropriately”: a “serious wrongdoing” under the PID Act.

Unfortunately, the Ombudsman interpreted our complaint as a “policy disagreement” and neglected to pursue the matter further.

In our open letter here to the NSW Ombudsman, we outline why our complaint qualifies as a much more serious Voluntary PID, constituting “serious wrongdoing”.

“Dear REDACTED,

Thank you for your response to my complaint regarding the NSW Ministry of Health, dated 6 May 2024.

Whilst you acknowledged that I made a Voluntary Public Interest Disclosure (PID), you decided it was not accepted as qualifying under the PID framework on the grounds that it was perceived primarily as a “policy disagreement”. In this letter I outline how my disclosure specifically points to procedural lapses and failures in data management and retention that have broad implications for public transparency and accountability, and which constitute “serious wrongdoing” under the Public Disclosures Act (2022) (“The PID Act”).

Nature of the Complaint

Voluntary Public Interest Disclosure:

The essence of my complaint does not stem from a mere “policy disagreement” but from identifying and reporting substantial administrative failures in the management and reporting of COVID-19 data by NSW Health, which according to the The PID Act, constitutes “serious wrongdoing”.

These substantial administrative failures include significant discrepancies in death counts, misclassification issues, and inconsistencies in hospitalisation data reporting. Such issues go beyond policy disagreement and highlight potential serious mismanagement that has and could continue to mislead public perception and policy decision-making: particularly for future pandemics when they arise.

These issues are crucial given that the data in question was used to justify extensive, unprecedented and extraordinarily intrusive public health measures such as lockdowns, isolation orders, mask and vaccination mandates.

The evidence of substantial administrative failures include:

Discrepancies in Death Counts: For the year 2022, NSW Health reported a total of 5,671 COVID-19 deaths, whereas the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) recorded only 3,607 deaths for the same period. Furthermore, there were six weekly reports from 2022 where the NSW COVID-19 Deaths exceeded total weekly Australian COVID-19 deaths: clearly an impossibility.

Misclassification of COVID-19 Hospitalisations and Deaths: There has been a consistent issue with how COVID-19 hospitalisations and deaths were classified. For instance, all hospitalisations were counted as “COVID-19 hospitalisations” regardless of whether the hospitalisation was due to COVID-19, despite assurances that these “back capture processes” would be stopped early in 2022.

Inflated ICU and Death Numbers: The practice of double-counting ICU patients as both in the ICU and as hospitalised patients contribute to an overstatement of the pandemic's severity. Deaths were categorised as COVID-19 deaths even when the virus was not the primary cause of death.

Such systemic errors in essential data reporting constitute "serious wrongdoing" under The PID Act because they reflect broader issues in governmental record-keeping and transparency. Under The PID Act “serious wrongdoing” is described as “government information contravention”, an example of which includes “systemic issues with an agency’s record-keeping system that means information is not being stored appropriately”.

In relation to the above, your letter references the judgement in the Ooi v NSW Ministry of Health case, suggesting that the “systemic errors” were acceptable and explained by this judgement because they were destroyed by NSW Health because of privacy concerns.

I disagree.

The judgement focused primarily on the Applicant's access to specific datasets for a limited period, where the issue was the Applicant’s access to the records used to produce the NSW Health Weekly Surveillance Reports. To clarify, I do not seek access to the individual, “patient level de-identified data” sought by the Applicant in the Ooi case. Rather, I am making a Voluntary PID about NSW Health’s data management which I believe contravenes its obligations under the State Records Act (1998) pointing to a serious ongoing failure to maintain essential health data appropriately. Therefore, the Ooi judgement cannot be appropriately used as a justification for NSW Health's failure to accurately maintain and manage COVID-19 data.

The Ooi judgement focused solely on denying an individual’s request for access to specific datasets, but importantly, did not exonerate NSW Health from its broader, statutory obligations to correctly keep records as required by law. This distinction is crucial, because unlike the Applicant in the Ooi case, I am not seeking data held (or formerly held) by NSW Health. Rather, I am making a Voluntary PID given the systemic failures of NSW Health to retain the essential data used to justify all manner of illiberal public health interventions.

The privacy considerations implied by your reference to the Ooi case are irrelevant anyhow. Had NSW Health retained the data used to produce those reports, it would have been compliant with its obligations under both the Health Records and Information Privacy Act (2002) and the Health Administration Act (1982), as well as the NSW Health Policy Directive “Data Collections – Disclosure of Unit Record Data Held for Research or Management of Health Issues”, all of which were relied upon by the Respondent in the Ooi case to justify their failure to keep the records as required. Each of these Acts and the directive provide for the allowance, and even in certain contexts, requirement for the retention of data to support ongoing public health management, research, and compliance with archival requirements. For example, the Policy Directive explicitly allows for the retention and use of health data, ensuring that data use aligns with both the protection of individual privacy and the facilitation of health services management and research. Therefore, maintaining this data could have been perfectly aligned with legal and ethical standards within NSW Health.

According to the State Records Act (1998), public offices are mandated to make and keep full and accurate records of their activities, including significant administrative actions involving public health data. The non-retention of such data, as described by Dr. Selvey in the Ooi case, raises questions about NSW Health's compliance with these record-keeping requirements.

Finally, the public interest in maintaining and disclosing accurate and detailed health data during the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be overstated. The unprecedented health crisis precipitated by the pandemic led to the implementation of significant and far-reaching public health policies such as lockdowns and mandates. These measures had and continue to have profound impacts on social, economic, and personal fronts. The maintenance of such data would allow for a thorough evaluation and review of the pandemic response, enabling policymakers, researchers, and the public to assess the effectiveness and proportionality of the actions taken. It also supports a transparent governance framework where decisions, especially those that restrict personal freedoms and affect millions, are made on a foundation of verifiable evidence.

To clarify, I understand and accept that NSW Health does not have to provide information or data, however, in my complaint with NSW Health I have never requested data from NSW Health. The Voluntary PID I am making relates to a “government information contravention” for “systemic issues with an agency’s record-keeping system that means information is not being stored appropriately”: in other words, a “serious wrongdoing”.

Failure to reply to correspondence

The second aspect of my complaint refers to the lack of any response from NSW Health, which I believe is within the ambit of the NSW Ombudsman. On your webpage, under the heading “types of complaints we handle”, “failure to reply to correspondence” is listed as the sixth subpoint.

In my complaint and in my initial correspondence with NSW Health, I requested an explanation, correction, clarification and/or acknowledgement of the data problems evident.

To date, I have not received a response from NSW Health, and therefore, made this complaint with the NSW Ombudsman.

Request for Reconsideration of Complaint Under PID Framework

First, I respectfully request that my complaint be reconsidered and properly classified as a Voluntary PID focused on administrative failures within NSW Health.

My intention is to ensure that these administrative concerns are addressed transparently, publicly and effectively, to uphold the integrity of public health reporting and policy formulation.

Second, I request your intervention to elicit a response from NSW Health to my inquiry given their failure to reply to my correspondence.

Thank you once again for addressing this important matter.

I look forward to your response and hope for a resolution that reflects the principles of accountability and transparency that are essential in public service.

Yours sincerely,

REDACTED”

>Unfortunately, the Ombudsman interpreted our complaint as a “policy disagreement” and neglected to pursue the matter further.

I am so sorry but I am genuinely laughing out loud at this.

Honk!