Have We Finally "Closed the Gap"?

Investigating the remarkably positive outcomes across the pandemic for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

On Sunday 29 August, 2021, an “unvaccinated” 51 year-old Aboriginal man from Dubbo, New South Wales, with “significant underlying health conditions” died in hospital.

His was Australia’s first Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) “COVID-19 death” from the cumulative 743 “COVID-19 cases” at the time: a case-fatality rate (CFR) of just 0.13%.

In contrast, Australian1 “COVID-19 deaths” at the time totalled 999, from 51,256 “COVID-19 cases”; a CFR of 1.95% (1348% larger than the ATSI CFR).

These incredible health outcomes with COVID-19 were completely unexpected. The “Gap” in life expectancy between Australian and ATSI peoples, which today is 8.8 years for males and 8.1 years for females (and is even wider in remote and very remote areas), it was anticipated, would be severely worsened by the pandemic. Allegedly, the risk of severe COVID-19 was up to four times that of the wider population, leading some scholars to claim “the oldest continuous culture on the planet [was] at risk”.

Despite the hyperbole, however, these alarmist predictions did not play out at all as expected.

In the period from 1 January to 24 October 2021, there were 15 ATSI “COVID-19 deaths” from 6,470 “COVID-19 cases”: a CFR of 0.23%.

In contrast, total Australian “COVID-19 deaths” in this same period were 728, from 130,120 total “COVID-19 cases”; a CFR of 0.56% - more than double the ATSI CFR.

Much later, by 28 January 2022, after the Omicron variant had arrived on Australia’s shores, carried by “fully vaccinated” travellers and spreading like wildfire through a “fully vaccinated” domestic population, total ATSI “COVID-19 deaths” had only reached 40 from 130,120 “COVID-19 cases”: the CFR had reduced to just 0.03%.

In contrast, in this same period, there were 3,496 Australian “COVID-19 deaths” from 2,246,513 “COVID-19 cases”; a CFR of 0.16% - more than 5.33 times larger than the ATSI CFR.2

In the period from the Omicron wave to 10 March 2024, total ATSI “COVID-19 deaths” had reached 451 “COVID-19 deaths” from 438,126 “COVID-19 cases”; a CFR of 0.10%.

In contrast, in the same period, there were 22,091 “COVID-19 deaths” from 11,148,348 “COVID-19 cases”; a CFR of 0.20% - double the ATSI CFR.3

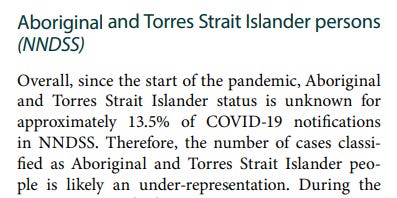

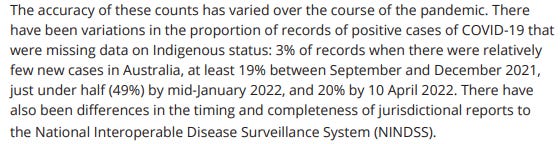

Due to under-reporting, it is likely that these positive outcomes were potentially even more positive than they appeared:

The under-reporting would mean that even more ATSI “COVID-19 cases” would have occurred relative to “COVID-19 deaths”, further reducing the CFR for ATSI peoples.

In ordinary circumstances, a remarkable outcome such as this should have dominated State press releases and legacy media bandwidth. “Gap Closure” has been pursued since 2008, regrettably with very limited successes; and so, the near total void of the acknowledgement of these positive outcomes with COVID-19 for ATSI peoples is perplexing.

What is also remarkable about these results with COVID-19 has been their persistence. While the Australian population has experienced continued “COVID-19 deaths” from 2020 onwards, with it becoming a leading cause of death in 2022 and 2023, these same outcomes were not evident for the ATSI population despite their lower rates of COVID-19 “vaccination” and assumed risks with severe COVID-19.

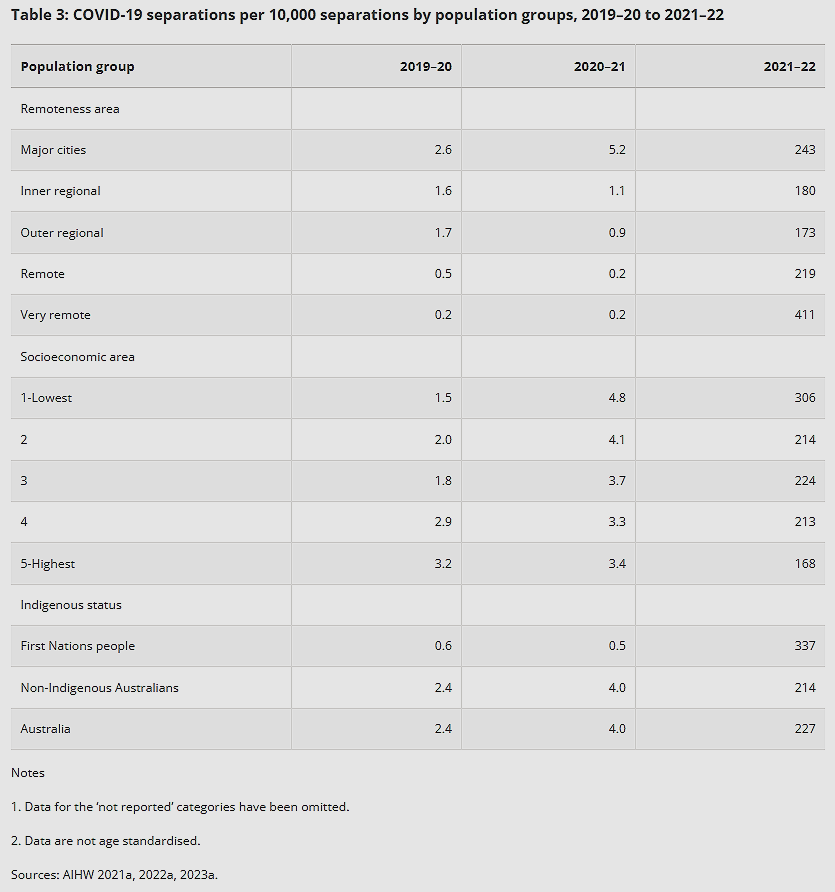

But it is also not just “COVID-19 deaths” which demonstrate a significant story about ATSI COVID-19 outcomes. Early in the pandemic (July 2019-June 2021), COVID-19 hospital “separations” (the conclusion of a hospital episode, which could mean a patient was either discharged [including transfers or discharges to other facilities] or died) were approximately the same between the ATSI and Australian populations and amounted to less than 0.1% of all “hospital separations” in this period.4

On reflection, the “curve” was impressively flattened. COVID-19 must have been treated somewhat effectively in the nation’s hospitals in 2020 at least, as “COVID-19 deaths” through this period were low, and those which occurred were predominantly in residential aged-care facilities. From July 2019-June 2021, although “COVID-19 hospitalisation” separations increased for most cohorts (also suggesting more “COVID-19 hospitalisations”), they actually reduced for ATSI peoples from 0.6 to 0.5 per 10,000 of the population.5 As the first ATSI “COVID-19 death” did not occur until August 2021, we know that these were all COVID-19 recoveries: not deaths.

In the next reporting period (July 2021-June 2022), however, coinciding with the Omicron wave, widespread “vaccine” uptake, coercion from mandates and the endorsement and uptake of multiple booster “vaccines”, there was a significant escalation of “COVID-19 hospitalisations” and separations for all cohorts:

Yet, again, ATSI peoples had far more favourable outcomes in this period than the Australian population. ATSI “COVID-19 hospitalisation” separations were 337 per 10,000 of the population, more than 57% better than the outcomes for the Australian population.

We know that ATSI “COVID-19 deaths” remained low throughout this period, whereas for the Australian population they did not, so we can be confident that these ATSI “separations” were not ATSI “COVID-19 deaths”. In contrast, the significantly greater number of “COVID-19 deaths” for the Australian population suggests that their “separations” included a substantial proportion of “COVID-19 deaths” more than recoveries. Therefore, even the “COVID-19 hospitalisation” outcomes were far more favourable for the ATSI population than the Australian population.

So, the lasting question is: did we close the “COVID-19 deaths” gap?

Perhaps, but it was not because of better “pandemic management” or State-led interventions.

As we show in this article these unexpected outcomes were the combined effects of:

Different demographics;

Lower rates of COVID-19 “vaccination”; and,

More accurate collection and reporting of ATSI COVID-19 data.

The conclusion we draw is that these astounding results with COVID-19 for ATSI peoples should prompt critical reflection from our health bureaucrats about our national response to COVID-19, their key health messaging and the harmful futility of the “vaccination” program.

Methodology

In this article we compare COVID-19 outcomes using CFRs rather than death rates because the CFR for each population provides a more accurate measure of how each cohort fared with COVID-19 among those who contracted the virus.

Death rates can misrepresent outcomes by including individuals who never contracted COVID-19, potentially understating the disease’s true impact. By concentrating on deaths relative to cases, the CFR provides a truer indication of each population’s actual COVID-19 outcomes.6

Different demographics

The different age distribution of the ATSI population can partly explain the different COVID-19 CFRs between the two populations.

In 2022, for example, 53% of all Australian “COVID-19 deaths” occurred in those aged over 85; an age significantly beyond the life expectancy for ATSI peoples. Therefore, other leading causes of death affecting cohorts younger than those typically impacted by COVID-19 reduced the possibility of more ATSI “COVID-19 deaths”.

The ATSI population is also much younger. As of 30 June 2021, an estimated 34% of the ATSI population was aged under 15, compared with 17% for the Australian population.7 People aged 65 years and over comprised 5.4% of the ATSI population, compared with 17.2% of the Australian population.8 Therefore, a comparatively greater aged proportion of the Australian population has resulted in more “COVID-19 deaths” in this cohort.

The different age distribution provides a compelling reason for these different COVID-19 outcomes, but one that would be difficult for our health bureaucrats to acknowledge. If age was the sole factor in these different outcomes, then it would provide evidence that COVID-19 was never a risk to younger cohorts; even the younger, supposedly more vulnerable ATSI population. Therefore, it cannot simply be the different age distribution that explains the more favourable ATSI COVID-19 outcomes.

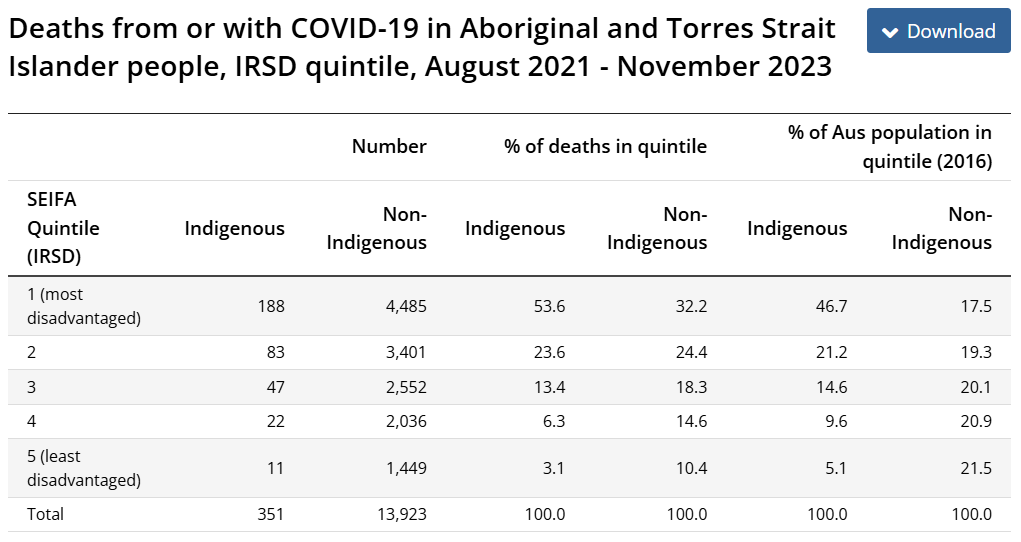

The different socioeconomic position (SEP) of ATSI peoples, provides yet another explanation for these different COVID-19 outcomes. Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows that of the relatively fewer total “COVID-19 deaths” in the ATSI population, the majority were in those from the lowest SEP:

As shown above, “COVID-19 deaths” among ATSI peoples were strongly associated with socioeconomic disadvantage rather than ethnicity. Beyond the most disadvantaged cohort, the percentage of ATSI “COVID-19 deaths” in each cohort was superior to that of the Australian population, with significantly lower “COVID-19 deaths” as a percentage of all deaths compared with the Australian population in each quintile.

Therefore, different demographics somewhat explain the different COVID-19 outcomes between the ATSI and Australian populations, but, we must also consider another important distinction between the two populations to explain these outcomes.

Lower rates of COVID-19 “vaccination”

ATSI peoples have not always been the most adherent to State messaging, with good reason, whether health messaging or otherwise. Historically, ATSI peoples have had lower rates of childhood vaccination for so-called “vaccine preventable diseases” and ATSI peoples are roughly five times more likely to “discharge [from hospital] against medical advice”.9

ATSI COVID-19 “vaccination” rates are also well below that of the Australian population. By September 2021, for example, ATSI first dose COVID-19 “vaccination rates were about 20% lower than the Australian population.10 By the end of 2021, only 63.5% of the ATSI population aged 12+ was “double vaccinated”.11 As of June 2024, 13% of the ATSI 18+ population were “unvaccinated”, and 26% of the 5+ population were “unvaccinated”.12 These lower rates of “vaccination”, it was anticipated, would lead to “devastating outbreaks . . . not only in remote regions, but in communities closer to towns and cities.”

Yet they did not.

COVID-19 “vaccination” rates continued to lag throughout the pandemic and never reached that of the Australian population. “Vaccination” coverage was even lower between ATSI peoples and the Australian population in remote areas. By September 2021, remote regions in Queensland and Western Australia had significantly lower “vaccination” coverage, with some remote regions with less than 10% “fully vaccinated”.13

Data also shows that ATSI uptake of booster “vaccination” was substantially lower compared with the Australian population. By February 2022, only 48.2% of the eligible ATSI population, compared with 63.4% of the Australian population had received “more than two doses”.14 By February 2023, only 56.6% of the eligible ATSI population had received “three or more doses” in comparison with 72.4% of the eligible Australian population.15

These trends of lower “vaccination” were spread across the nation in 2023. Although the Department of Health and Aged Care’s “COVID-19 Vaccination - Geographic Vaccination Rates - LGA - Indigenous Population” webpage has been scrubbed from the Internet, it is still available on the Internet Archive. The most recently updated data, from 16 March 2023, showed that the ATSI population in each Local Government Area (LGA) had “vaccination” rates well-below that of the Australian population. The further away from urban areas, these rates dropped even further in terms of the number of “vaccines” given too.16

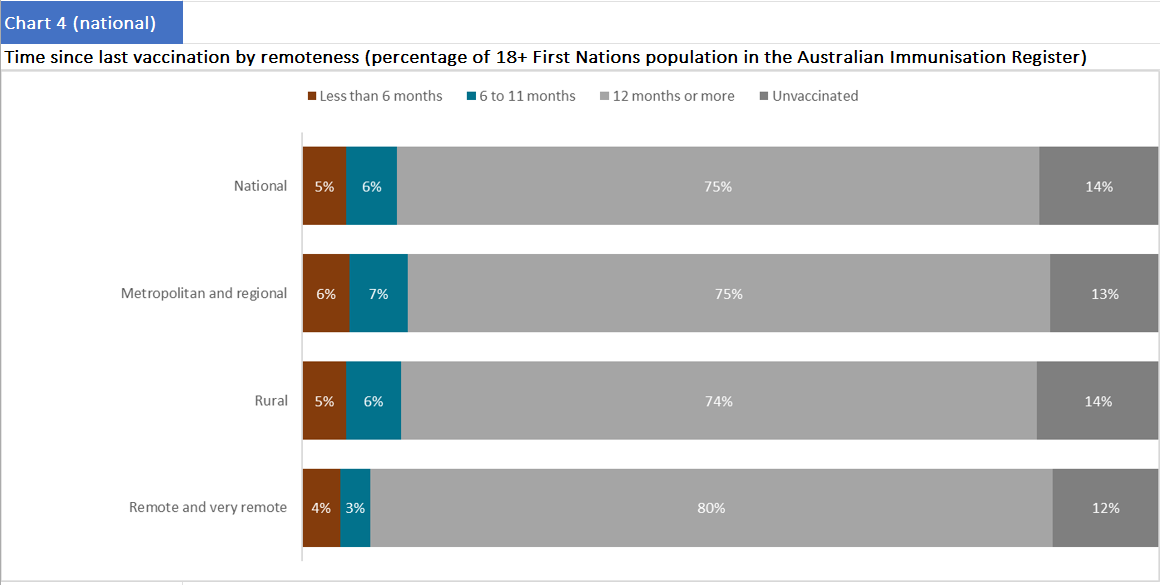

ATSI peoples not only had less “vaccination” coverage, but also longer “time since last ‘vaccination’” across all areas:

Data from November 2023 (shown above) revealed that more than three-quarters of the ATSI population had received their last COVID-19 “vaccination” more than one year prior.

In sum, the data shows how the ATSI population had far lower rates of COVID-19 “vaccination”, including booster “vaccination”. The data also shows that the further away from major cities, “vaccination” coverage dropped further still, with the potential to seriously compound existing health inequalities. Therefore, ATSI “COVID-19 deaths” should have been significantly higher than they were in remote areas because of this added layer of presumed disadvantage.

But they were not.

We contend that the reduced rates of “vaccination”, particularly booster doses, have likely contributed to more favourable ATSI COVID-19 outcomes. There is ample evidence in the literature pointing to negative vaccine effectiveness and documented vaccine harms, not to mention findings that COVID-19 itself was relatively mild in most cases. Therefore, every injection of a COVID-19 “vaccine” added risk to the ATSI population through increased susceptibility to contracting COVID-19 or harm from the “vaccine” itself. By avoiding these risks, it also can explain their favourable COVID-19 outcomes.

If our contention is incorrect, then these unexpected outcomes must be explained by health bureaucrats and academics who insisted that the absence of “vaccines” would result in far worse outcomes for ATSI peoples. The observational data provide strong evidence that lower rates of COVID-19 “vaccination” were unexpectedly protective for ATSI peoples.

More accurate collection and reporting of ATSI COVID-19 data

The third explanation for these favourable ATSI COVID-19 outcomes is that ATSI COVID-19 data was a more accurate reflection of the severity of COVID-19 disease than Australian COVID-19 data. There are several reasons supporting this speculation:

“COVID-19 hospitalisations” and “COVID-19 deaths” data for the Australian population were exaggerated through:

Counting all “incidental” hospitalisations “with” COVID-19 as “COVID-19 hospitalisations”;17

Double-counting all “COVID-19 hospitalisations”. For example, an ICU admitted “COVID-19 hospitalisation” was counted as both a “COVID-19 hospitalisation” and a “COVID-19 ICU admission” during the pandemic;18 and,

Misclassification of “COVID-19 deaths” even when COVID-19 was not the cause of death.19

This methodology would have similarly impacted COVID-19 data for ATSI peoples; however, due to their smaller population size - approximately 3.8% of the Australian population - these numbers were not amplified to the same degree. Consequently, the distortion of data resulting from these practices was more pronounced at the broader Australian population level, making the overall COVID-19 data for the Australian population appear significantly worse in comparison with the ATSI population;

Lower rates of “COVID-19 hospitalisations” among ATSI peoples reduced the opportunity for exaggerated data, such as incidental “COVID-19 hospitalisations” or “COVID-19 deaths” being misclassified; and,

There was a contrasting political imperative to downplay COVID-19 severity within ATSI populations, as presenting improved health outcomes aligned with the broader “Closing the Gap” agenda. The higher proportion of incidental “COVID-19 deaths” in the ATSI population compared with the Australian population suggests COVID-19 was unexpectedly less lethal for ATSI peoples. Between August 2021 (the first ATSI “COVID-19 death”) and January 2024, approximately 40% more of the “COVID-19 deaths” were recorded as “with” COVID-19, not “from” COVID-19.20 COVID-19 would have been causative for many more ATSI “COVID-19 deaths” if the presumed risks with COVID-19 were greater for ATSI peoples. It is, therefore, plausible that the larger number of deaths “with” COVID-19 for ATSI peoples might be a truer reflection of COVID-19’s actual lethality.

Conclusion

These unexpected and persistently favourable ATSI COVID-19 outcomes demand that we revisit the broader national response to the pandemic and its central assumptions. Demographics played some role, but importantly, so too did lower rates of COVID-19 “vaccination” combined with more accurate data collection and reporting.

It is now incumbent upon those who issued ominous forecasts for ATSI peoples to explain how and why the predicted catastrophe never came to pass. The evidence shows that we have some crucial lessons to learn from what happened with ATSI peoples and COVID-19 which should guide our future pandemic planning.

Postscript

In researching this article, we were surprised to learn that a collection of academics had addressed the dramatic reversal of “The Gap” in a polemic published in The Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health.21

The brief article attributed the favourable ATSI COVID-19 outcomes to “outstanding Indigenous leadership” and the application of “world’s best practices” but it failed to detail the specific strategies or actions taken. For instance, it mentioned that Aboriginal health leaders implemented best practices across various locations but did not elaborate on the specifics of what these practices entailed, how they were executed, or why they provided superior outcomes to the Australian population.

While the thought-bubble references the low number of “COVID-19 death” and “COVID-19 hospitalisation” rates among ATSI peoples, it does not address the demographic variables or different rates of “vaccination” which more plausibly explain these outcomes.

More concerningly, the authors make several unsubstantiated and unscientific claims, suggesting that ATSI peoples’ allegedly superior pandemic management provided evidence that a Voice enshrined in the Constitution would work. The article’s tone, language, and selective emphasis on this last theme suggest a primary goal of advancing a political narrative, rather than critically and scientifically unpacking the pandemic’s impact on ATSI populations.

“[O]utstanding Indigenous leadership, governments at all levels listen[ing] to Aboriginal wisdom and that control was handed to those who knew what to do. . . This viewpoint makes the case for a different model to engage and empower First Nations to really close the gap ‐ themselves”. . . I hope non‐Indigenous Australia finally learns is that Indigenous leadership – when left to genuinely flourish without the ever‐present interference and paternalism – is phenomenally powerful, deeply impactful and highly successful, highlighting the ways of knowing, doing and being that exist in Indigenous Australia” [emphasis added]

Had these authors considered the practical implications of what “flourishing” looks like without the “ever-present interference and paternalism”, they may have stumbled on the answer that COVID-19 “vaccination” might have been among the two most important reasons why ATSI peoples’ COVID-19 outcomes had been so favourable.

In this postscript, we critically analyse the claims made in the article, further supporting our main contention in our article that demographics, different rates of COVID-19 “vaccination”, and more accurate COVID-19 data collection and reporting were the reasons for these more favourable outcomes.

“Australian First Nations response to the pandemic: A dramatic reversal of the ‘gap’”: a response

According to the article authors, the roadmap to these ATSI successes were based on four key pillars: the right to self-determination and leading coordination in the COVID-19 response; increasing the supply of housing; Indigenous data sovereignty; and building local capacities for healthcare delivery with ATSI health practitioners.22

Yet, these were largely the same, if not inferior initiatives, in comparison with those imposed on the Australian population, with the exception of the right to self-determination and to lead coordination in the COVID-19 response. Therefore, we challenge the article authors’ conclusions by addressing each of their separate claims below.

The right to self-determination and leading coordination in the COVID-19 response:

Referencing the work of others, the article authors describe how these measures included “prohibiting access permits for non-essential travellers and developing key distancing health messages in local languages and Aboriginal community-controlled health services developing local preparedness and response plans”.23 Communities themselves also “imposed restricted travel to and from communities”, implementing “considerable efforts to protect elders, and found solutions to secure isolation and quarantine facilities where housing stock [was] limited”.24

As important as self-determination might be for ATSI people in general, it is highly unlikely this first aspect of the approach could explain the much better COVID-19 health outcomes for ATSI peoples for the following reasons:

First, this aspect sounds very much like an endorsement of lockdowns for the prevention of severe COVID-19 outcomes, with the notable difference that at least this version was driven by communities and not by the State. But everyone in Australia had lockdowns: some more than others and for longer too. So, the argument that this brand of lockdowns were more effective for the ATSI peoples and not others is unconvincing and requires evidentiary support.

Second, more than 86% of the ATSI population live in “non-remote” areas and would have not been in a system with “community-determined lockdowns” as those suggested by the article authors. Therefore, these approaches cannot explain the different CFRs between the two populations.

Third, if self-determination was effective at preventing “COVID-19 deaths”, the article authors do not explain why it was ineffective at preventing “COVID-19 cases”. ATSI “COVID-19 cases” still found their way to ATSI peoples in urban, remote and very remote areas and it did not cause as many deaths in comparison with the Australian population. The severity of each individual “COVID-19 case” was not determined by lockdowns, lockouts, border controls, or other movement restriction policies for the individual who contracted each “case”. Rather, it was determined by the virus itself, access to early treatments and the age and health of the person who contracted the “case”.

Fourth, if ATSI peoples had better outcomes because they were able to create more “localised pandemic responses” developed by their communities, then why was this benefit not observable in the Australian population who, if the argument holds, have this by default as their birth-right?

Finally, it is difficult to assess the extent to which developing key distancing health messaging, or any health messaging for that matter might have been impactful given the lagging “vaccination” rates and adherence to other “health” practices during the pandemic, particularly if they bore any resemblance to this attempt by the (then) Western Australian Premier Mark McGowan to translate his key health messages:

An immediate increase in the supply of housing:

The article authors never interrogate reasons why this approach was successful for the ATSI population in comparison with the Australian population, who have access to the supply of housing to have provided adequate quarantine/isolation. It is obvious, from the suggestion that the supply of housing was deficient in ATSI communities at some point during the pandemic to have warranted the recommendation for this intervention to increase its supply. Therefore, rather than providing a sound reason for why the COVID-19 outcomes were better for ATSI peoples, it provides a sound reason for why they should not have been.

Indigenous data sovereignty:

“Indigenous data sovereignty” is explained as data collection that is “comprehensive”, “shar[ed] to all parties”, “sensitive to all parties” and in a “timely manner”.25 The article authors suggest “data sovereignty” includes:

“[A] rights-based approach aimed at effective Indigenous data governance to ‘empower our peoples to make the best decisions to support our communities and Indigenous in the ways that meet our development needs and aspirations’.”26

But the recommendation is purely aspirational and does not satisfactorily distinguish the approach taken for the Australian population. There is no evidence supporting the contention that the majority of the ATSI population had the freedom to exercise their “rights-based” approach that was either any different to the Australian population, or to an extent that was influential as far as COVID-19 outcomes were concerned, whether for the remote or “non-remote” ATSI populations.

Building local capacities for healthcare delivery with ATSI health practitioners

This presumed fourth pillar suggests that strengthening ATSI health workforces was essential to these favourable COVID-19 outcomes, though the article authors do not address this aspect of the roadmap in any detail whatsoever. In the original study, it was suggested that increasing and retaining ATSI health practitioners, building infectious disease expertise, and developing surge workforce plans would ensure better COVID-19 outcomes; however, this argument relies heavily on a “deficit” model (like pillar # 2), which assumes that gaps in health workforce capacity hindered ATSI communities’ capacity to manage the pandemic effectively. The premise suggests that improvements were necessary for better outcomes to emerge. Yet the reality of far more favourable COVID-19 outcomes for ATSI populations compared with the broader Australian population directly contradicts this notion. If workforce deficiencies were a major limiting factor, ATSI communities should have experienced worse outcomes, not significantly better ones.

Postscript conclusion

The article’s central claims remain inadequately substantiated. Demographic variations, differential “vaccination” rates, and more comprehensive data collection practices offer far more plausible explanations for the gap in COVID-19 outcomes between ATSI peoples and the Australian population. By centring their argument on allegedly superior ATSI leadership and community-led initiatives, the authors’ case is unscientific and unconvincing and the reasons we propose in this article are more valid conclusions for the more favourable ATSI COVID-19 outcomes observed.

In this article, when we write “Australian”, we are referring to all Australians excluding the ATSI population. One does not define ethnicity by what one is not. Therefore, we choose to not use the term “non-indigenous” to describe the Australian population.

Furthermore, what complicates our analysis in this article when we compare “ATSI” and “Australian” populations is that tracking who is and is not ATSI in Australia presents significant challenges. ATSI identity is self-determined, with individuals identifying based on ancestry, community recognition, and personal affirmation, rather than through any formal national test or registry.

While this approach respects the diversity and autonomy of ATSI peoples, it introduces difficulties for statistical accuracy which could mean the CFR could be impacted.

See https://covidlive.com.au/report/daily-cases/aus for “COVID-19 cases” and https://covidlive.com.au/report/daily-deaths/aus for “COVID-19 deaths” data used to make these calculations.

Department of Health and Aged Care, “COVID-19 Australia: Epidemiology Report 85 Reporting Period Ending 10 March 2024”, Communicable Diseases Intelligence, Volume 48, 2024, p. 3.

AIHW, “COVID-19”, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/covid-19, Table 2, accessed 28 January 2025.

We know that these “separations” were not “COVID-19 deaths” too because we have that data showing ATSI “COVID-19 deaths” were very low through this period.

We maintain, however, that even if we were to use death rates as the metric to compare these outcomes, much larger gaps in death rates for other leading causes of death compared with “COVID-19 deaths” (particularly in major cities, and inner and outer regional areas) were present in the ATSI population and the same, unexpected reduction in the “gaps” with “COVID-19 deaths” are unexplained.

AIHW, “Profile of First Nations People”, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/profile-of-indigenous-australians, accessed 26 January 2025.

AIHW, “Dementia in Australia”, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/dementia/dementia-in-aus/contents/understanding-dementia-among-first-nations?, accessed 26 January 2025.

We acknowledge that higher rates of “Discharge Against Medical Advice” in ATSI populations might explain the higher rates of “separations” addressed earlier in the article. It would not, however, explain the lower numbers of “COVID-19 deaths” in ATSI populations.

ABC News, “Why is the Indigenous COVID-19 vaccination rate 20 per cent lower than the national average?”, https://archive.md/9ZOp1#selection-725.0-725.197, accessed 24 January 2024.

Australian National Audit Office, “Australia’s COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout”, https://www.anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/australia-covid-19-vaccine-rollout, accessed 26 January 2025, (archive link).

Department of Health and Aged Care, “First Nations COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage – National data – 14 June 2024”, https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-06/first-nations-covid-19-vaccination-coverage-national-data-14-june-2024.xlsx, sheet 2, chart 2 and 3, accessed 26 January 2025.

National Indigenous Times, “Experts Warn Indigenous Vaccination Rates Must Increase before Reopening Country”, https://nit.com.au/10-09-2021/2339/experts-warn-indigenous-vaccination-rates-must-increase-before-reopening-country, accessed 28 January 2025, (archive link).

More comprehensive data from the next fortnight in September 2021 is available via the Internet Archieve here: https://web.archive.org/web/20210923114234/https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/09/covid-19-vaccination-geographic-vaccination-rates-sa4-indigenous-population-22-september-2021.pdf

Department of Health and Aged Care, “COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout Update – 28 February 2022”, https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/02/covid-19-vaccine-rollout-update-28-february-2022.pdf, p. 3, accessed 26 January 2025.

Department of Health and Aged Care, “COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout Update – 24 February 2023”, https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-02/covid-19-vaccine-rollout-update-24-february-2023.pdf, p. 3, accessed 26 January 2025.

Although estimates for the population in remote and very remote areas are given which may potentially have led to undercounts of the number of “vaccines” administered, these are likely to be negligible in impacting the comparison with the Australian population, if at all, given such low numbers.

These data can be reviewed here: https://web.archive.org/web/20230528222542/https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-03/covid-19-vaccination-local-government-area-lga-indigenous-population-17-march-2023.pdf

Disclaimers such as these are included in many of the NSW Health Weekly Surveillance Reports:

“People with COVID-19 can be hospitalised because of the disease but may also be hospitalised for other reasons not related to their COVID-19 diagnosis. For the purposes of surveillance, reported hospitalisation counts include all people who were admitted to any hospital ward, including emergency departments, around the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis. This does not mean that all the hospitalisations reported are due to a worsening of COVID-19 symptoms. The count does not include people managed in the community (e.g., including Hospital in the Home schemes).”

Although NSW Health respiratory surveillance methodology may not be representative of a national approach, it provides a useful insight into how COVID-19 data was collected and reported in Australia’s largest State.

The NSW Health Weekly Surveillance Reports have been merged into one large .pdf document for review. Search the glossary or hospitalisations data in this document here.

Disclaimers such as these are also included in the NSW Weekly Surveillance Reports:

“Note, these categories are not mutually exclusive. Hospitalised includes cases admitted to ICU; deaths may occur with or without being admitted to hospital or ICU.”

These have been merged into one large .pdf document for review in this document here.

Disclaimers such as these are also included in the NSW Health Weekly Surveillance Reports:

“Reported deaths were classified as COVID-19 deaths if they met the surveillance definition in the Communicable Diseases Network of Australia’s COVID-19 National Guidelines for Public Health Units. Under this definition, deaths are considered COVID-19 deaths for surveillance purposes if the person died with COVID-19, not necessarily because COVID-19 was the cause of death.”

These have been merged into one large .pdf document for review in this document here.

The 34.5% of ATSI deaths “with” COVID-19 is 41.39% larger than the 24.4% of Australian deaths “with” COVID-19.

ABS, “COVID-19 Mortality in Australia: Deaths Registered until 31 January 2024”, https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/covid-19-mortality-australia-deaths-registered-until-31-january-2024#covid-19-mortality-among-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people.

Stanley, F., Langton, M., Ward, J., McAullay, D. and Eades, S., “Australian First Nations Response to the Pandemic: A Dramatic Reversal of the ‘Gap’, Journal of Paediatric and Child Health, 57: 1853-1856, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15701.

The article authors cite the following study for the roadmap:

Moodie, N., Ward, J., Dudgeon, P., Adams, K., Altman, J., Casey, D., Cripps, K., Davis, M., Derry, K., Eades, S., Faulkner, S., Hunt, J., Klein, E., McDonnell, S., Ring, I., Sutherland, S., & Yap, M., “Roadmap to Recovery: Reporting on a Research Taskforce Supporting Indigenous Responses to COVID-19 in Australia”, The Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), 4–16, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.133.

Ibid., p. 7.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Stanley, F., op. cit., p. 3.