Exposing the Myths of Australia's Hydroxychloroquine Restrictions

Evidence proves that the fears about safety and shortages did not drive the TGA's decision to restrict the supply of hydroxychloroquine on 24 March 2020.

In early 2020, hydroxychloroquine was being used as a treatment for COVID-19 in protocols developed by courageous doctors like Vladimir Zelenko and Paul Marik. Hydroxychloroquine’s positive results were also being published in the academic literature.

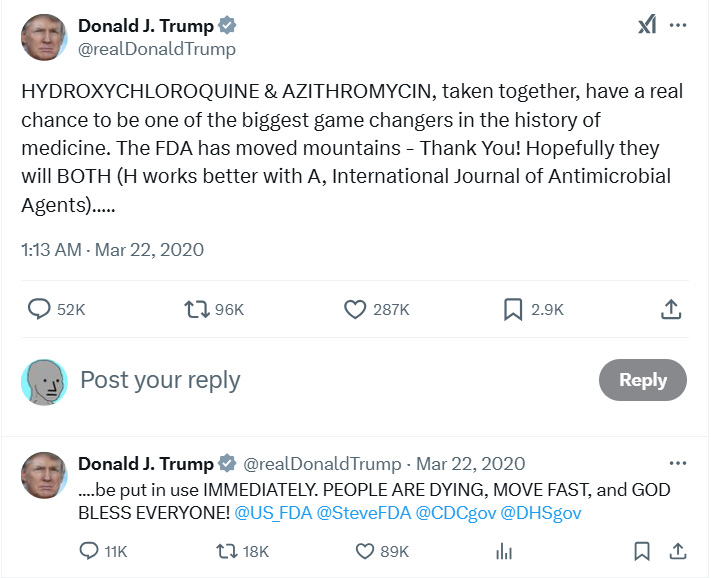

Yet, it was not until a 20 March 2020 press conference where President Trump gave hydroxychloroquine a very public endorsement (despite the best efforts of Anthony Fauci to water it down) which rocketed it to popularity.

Globally, the surge in hydroxychloroquine’s popularity from this press conference was the catalyst for the commencement of a coordinated global takedown by the Bio-Pharmaceutical Industrial Complex, combining legacy media propaganda with the efforts of financially compromised and institutionally aligned researchers under its influence.1 Under U.S. law, an Emergency Use Authorisation (EUA) for a vaccine or therapeutic can only be granted if there are no adequate, approved and available alternatives for diagnosing, preventing, or treating the disease or condition. Therefore, the promise of hydroxychloroquine was the prime threat to any future EUA granted to the “vaccines” being “warp-sped” into production at the time.

In Australia, a series of logistically impossible events were also set in motion by this press conference, which could not have happened organically. Within a matter of days, practically every State and Territory in Australia were locked down for the first time, and by 24 March 2020, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) had responded to “reports” of alleged increased “off-label” (meaning for an indication not approved by the TGA) prescribing of hydroxychloroquine by removing the authority of doctors (with the exception of some specialists) to issue new prescriptions for patients without the registered indications for the medicine.

The TGA cited concerns of safety risks and shortages in making its decision. Yet, our investigation of the TGA’s Database of Adverse Event Notifications (DAEN) matched against the Department of Health’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) prescriptions data for the same period reveals that these concerns about hydroxychloroquine’s safety were unfounded, and our analysis of historical data from the TGA’s “Medicines Reports Shortages Database” shows that no shortage of hydroxychloroquine occurred until much later in 2020; even following the logistically fanciful surge in demand for the medicine in March 2020.

The conclusions we draw in this article, therefore, are that the decision to restrict access to hydroxychloroquine had very little to do with safety or risks of shortages.

While we are sure everyone is well aware of the broader debates surrounding this issue, the intention here is to provide evidentiary support to expose the myths underpinning the TGA’s intervention in restricting access to a vital treatment which could have prevented lockdowns; masks; “vaccination” mandates; and above all, could have saved Australian lives.

The safety of hydroxychloroquine

In reviewing the TGA’s DAEN for adverse events relating to hydroxychloroquine, we found very few examples showing significant adverse events linked with the medicine which could have warranted the TGA restrictions.

First, there was not one single adverse event report citing “off-label” use for hydroxychloroquine in the period from 18 April 2019 to 18 June 2020.2 This means that the restriction was imposed on the basis of the presumption of an apparent risk using the medicines, not because of increased, or extensive DAEN reports.

Second, the first “off-label” adverse event report for hydroxychloroquine (occurring 18 June 2020) included many other medicines, raising the possibility that hydroxychloroquine might not have even caused it or the other adverse events where many other medicines were listed in other reports. In fact, there are very few adverse event reports where “hydroxychloroquine sulfate” is listed as the “single suspected medicine” with few exceptions.

Let’s take a brief detour here to explore these exceptions where hydroxychloroquine was reported as the “single suspected medicine” in DAEN:

The last DAEN report for hydroxychloroquine as the "single suspected medicine" prior to the TGA-imposed restrictions of March 2020, was 18 August 2019.

There are only a handful of instances where hydroxychloroquine is reported as the "single suspected medicine" in causing an adverse event in the entire reporting period from the first report in 1985 to the most recent in December 2024.

Yet, quite strangely, it appears there were several unfortunate days where some form of hydroxychloroquine-bingeing occurred, causing all manner of harm (occurring after the restrictions were imposed):

- 29 April 2020: 22 "Females" and 2 "Males" with ages ranging from 34-88 who attended the first hydroxychloroquine-binge party suffered "Maculopathy" and "Retinal Toxicity" with another 13 of these same people experiencing "Retinal Depigmentation".

- 12 May 2020: Not heeding the warnings, another 23 "Not specified" people and one "Female" succumbed to the wonderdrug again, once again ending up with "Maculopathy" and "Retinal Toxicity". One of these 24 people also suffered "Toxicity to various agents" from this second hydroxychloroquine-binge event.

- 27 December 2022: 23 "Females" and 2 "Males" this time suffered "Retinal Toxicity" and "Retinopathy" from, yes you guessed it, the "single suspected medicine": hydroxychloroquine.

~ Source: TGA, DAEN, Google Sheet, column E, adverse events reports with a single suspected medicine are highlighted in orange.

These dates with multiple entries on the same day are the only occasions in the entire history of DAEN reports for hydroxychloroquine where more than three reports occurred on the same date. Third, prior to the imposition of the restrictions, there were relatively few of the “significant adverse event[s]” reported to DAEN for hydroxychloroquine as the “single suspected medicine”.3 Keyword searches for these adverse events were conducted in DAEN returning the following:

“Cardiac”: three reports, one in which the single suspected medicine was hydroxychloroquine; 2005, 2009 and 2017;

“Cardiomyopathy”: three reports, all of which the single suspected medicine was hydroxychloroquine; 994, 2007, 2012;

“Hypoglycaemia”: no reports;

“QT”: two reports, none of which where hydroxychloroquine was the single suspected medicine; 2014, 2019;

“Retinal”: 13 reports, 12 of which where hydroxychloroquine was the single suspected medicine ; 1977, 1988, 1996, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2016, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2019.

The above list is not exhaustive, but it provides further credence to the argument that the alleged risks of hydroxychloroquine were overstated and that its safety profile had been sufficiently established with very few reports of significant adverse events, particularly in the period between the pandemic commencing and the TGA’s 24 March 2020 intervention.

Fourth, the incredibly small numbers of adverse event reports relative to the number of prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine reveal just how rare these adverse events reports are. Here we run the risk of sounding like the TGA to prove a therapeutic’s safety by calling to attention the number of doses relative to the few adverse event reports. We acknowledge that DAEN does not capture all of the potential adverse event reports because of the“underreporting rate”, which some estimate to be as high as 99%.4 However, rather than simply rely on this contention alone to prove the safety of the drug, it adds to our three preceding points in this argument that hydroxychloroquine is, and was demonstrably safe.

Fifth, we have good reason to believe that safety is evidently not one of the TGA’s primary concerns when deciding to restrict access to medicines, given its continued promotion of COVID-19 “vaccines” despite the extraordinary number of adverse events reported in DAEN linked with their use. So, the TGA’s apparent concerns about the presumed risks of hydroxychloroquine are inconsistent with its approach to the COVID-19 “vaccines” and we have very good reasons to disbelieve this justification for its intervention.

Finally, even if we accepted the TGA’s pernicious argument about the potential for harms caused by “off-label” prescribing of hydroxychloroquine, its intervention undermined trust in medical professionals, disrupting the doctor-patient relationship and denying a proven safe and effective early treatment for COVID-19 to Australians.

In sum, there are very good reasons to believe that the decision to restrict access to hydroxychloroquine on 24 March 2020 had little to do with concerns about its safety.

The risk of potential shortages of hydroxychloroquine

Aside from concerns about the safety of hydroxychloroquine, the TGA also expressed concerns about potential shortages which could result from increased “off-label” prescribing.

We reviewed the PBS data for 2020 and learned that despite an extraordinary near 100% increase in the number of prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine in March 2020, there was a continued uninterrupted supply of the medicine in this period:

As shown above, the number of prescriptions recorded in Australia’s PBS “Date of Supply” data revealed an unprecedented spike in the number of hydroxychloroquine prescriptions for March 2020, but, again, no shortage followed in April 2020.

Historical data from the TGA’s “Medicines Reports Shortages Database” reveals that the only shortages which occurred for hydroxychloroquine during the pandemic occurred many months after the restrictions were imposed.5 The first shortage for hydroxychloroquine commenced 24 August 2020 and ended almost a month later on 21 September 2020. It occurred because of “Other” and was rated “Medium” in impact (out of three options including “Critical” or “Low”). The second shortage for hydroxychloroquine (for a different brand of the medicine) commenced 3 September 2020 and ended 9 October 2020 and was rated “Low”. The second shortage, curiously, was caused by “Unexpected consumer demand”.

It would appear, therefore, the TGA’s decisive action averted any potential shortages for hydroxychloroquine at the time the restrictions were imposed, yet, we question the integrity of the PBS data for hydroxychloroquine in March 2020 and the claims that “off-label” prescribing was driving the allegedly “unprecedented demand” for the drug.

The integrity of the PBS data

There are several reasons to be doubtful of the integrity of the PBS data and claims that it was driven by “off-label” prescribing because interest in hydroxychloroquine could only have surged in Australia in a matter of days prior to the imposition of the TGA’s restrictions.

First, it would be uncontroversial to state that ordinary Australians do not base their health decisions on what has been published in the academic literature. Even if they did, there were very few studies proposing the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19 before the imposition of the TGA restrictions. The earliest study was published on 19 February 2020, but the most influential preprint was published much later, on 20 March 2020. Despite the growing interest in hydroxychloroquine in academic circles, it was highly unlikely that interest in hydroxychloroquine could have been driven by ordinary Australians’ attention to these studies. Even if ordinary Australians had been paying attention to scientific discourse, it was not until much later in March when this influential preprint was published, and only three days before restrictions on hydroxychloroquine were imposed. Therefore, it is improbable the surge in interest in hydroxychloroquine could have been driven by these developments in academia and the surge in demand for the medicine must have had another cause.

Second, the spike in interest in hydroxychloroquine occurred so late in March that it was a logistical impossibility for Australians to have sought and obtained prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine. This spike was caused by President Trump’s endorsement of the medicine in two consecutive press conferences, the first on 19 March 2020 where he called it a potential “game changer” and another glowing endorsement on March 20 2020 (shown below):

These were the first public promotions of hydroxychloroquine from important figures outside of academia which would have drawn attention to the medicine. In the press conferences Trump (and Fauci albeit begrudgingly) affirmed the established long-term safety of hydroxychloroquine and its promise, even if “anecdotal”, for treating COVID-19. Two days after this press conference, Trump tweeted about the previously mentioned influential preprint, drawing further attention to hydroxychloroquine:

Undoubtedly, these public endorsements would have piqued the interest of people scared of COVID-19 who were desperate for a cure, but we question the extent to which this interest could have created the surge in demand reported in the PBS data, particularly given the implausibly tight timeline.

Trump’s second press conference occurred in Washington D.C. on Friday 20 March 2020 at 11:50am EDT (Saturday 21 March 2020, 2:50am AEDT). Realistically, how many people would have woken to their morning coffee several hours later, seen this news, rushed to their general practitioner (GP) requesting “off-label” hydroxychloroquine prescriptions? Did this really happen on the weekend of Saturday 21 March to Sunday 22 March 2020?

What makes the reported surge in hydroxychloroquine prescriptions even more extraordinarily unbelievable is that the TGA restrictions were imposed on 24 March 2020. Australians, therefore, had approximately four days, two of which spanned a weekend, to see the news and demand their hydroxychloroquine fix: an impossible window of opportunity for 25,653 extra, allegedly “off-label” prescriptions for March 2020 to have been issued.

The third reason for disbelieving the data showing a surge in demand for hydroxychloroquine is that most of the legacy media were late to catch-up with this “news” to report on it, and therefore, to influence consumer behaviour to the extent reported. We have conducted searches of Australia’s major legacy media publications for articles using the keyword “hydroxychloroquine” from January 1st 2020 to March 23 2020 (the day before the TGA restrictions were imposed) which returned only limited results. The earliest legacy media article in Australia mentioned chloroquine, published in a Daily Telegraph article on 18 March 2020. Hydroxychloroquine as a potential treatment for COVID-19 then appeared in The Guardian on 19 March 2020, and several News Corporation publications on 20 March 2020. Based on results from our search, there were so few legacy media articles early in March which could have influenced the demand for hydroxychloroquine to the enormous extent reported for the entire month. The reported surge in demand must have coincided with the publication of these articles, but the sheer increase in the number of prescriptions relative to the previous month defies logic.

The fourth reason we have for calling the integrity of the PBS data into question is that Australia had just entered its first “COVID-19 wave” at the time. Face-to-face consultations with GPs were discouraged, and those with COVID-19 symptoms were encouraged to get PCR-tests prior to doing virtually anything. At the time, PCR-test results were returned via SMS no sooner than 48 hours, likely limiting the number presenting to their GP to request a hydroxychloroquine prescription. Although telehealth services had been expanded so people did not have to leave their homes, telehealth appointments accounted for only 15% of all GP presentations for March 2020. So, not only did Australians have a limited window to have learned about hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19 following Trump’s press conference and the slow catch-up of the legacy media, but they also had reduced access to their GPs to obtain prescriptions for the medicine to the level reported in the PBS data.

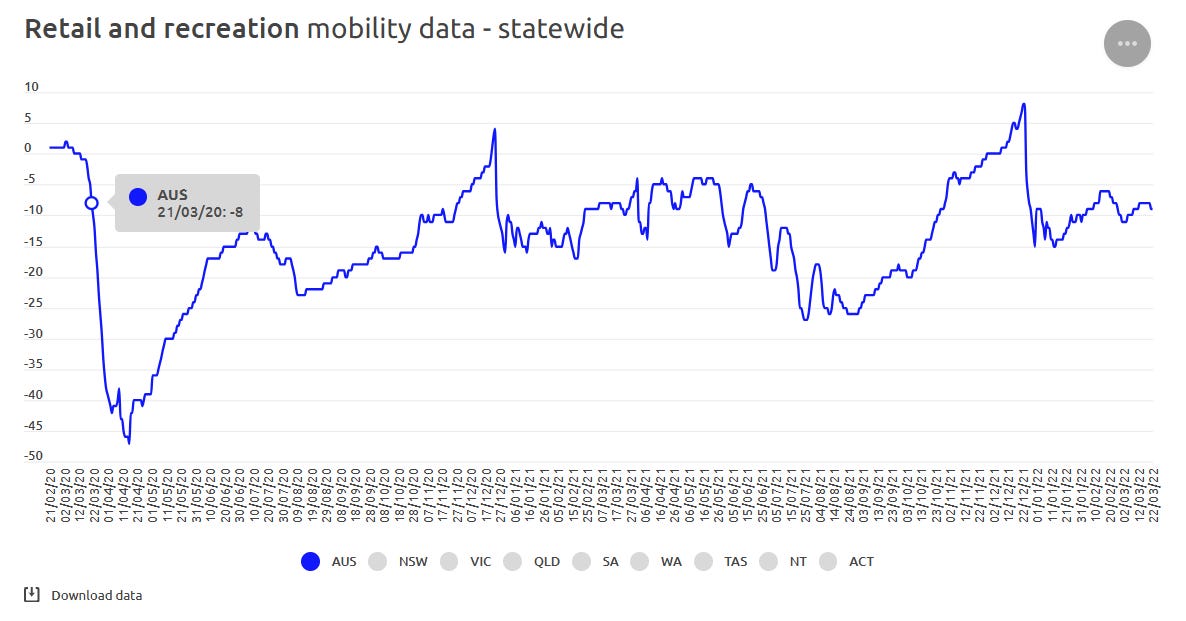

A fifth reason to disbelieve the prescriptions data for hydroxychloroquine for March 2020 is the reduced community movement at the time. “COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports” reveal that the commencement of the first COVID-19 wave had caused a reduction in community movement in “retail and recreation” spaces where GPs are often located.

So, not only did Australians have an implausibly narrow window to learn about and seek prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine, they were facing increasingly fear-based messaging from the State and were on the cusp of the first “two weeks to slow the spread” lie. Surely, fear might have driven some people to present to their GP, or book a telehealth appointment to find the only available “cure” at the time, but we question the extent to which these prescriptions could, or would have been given by prescribers in the timeframe suggested.6

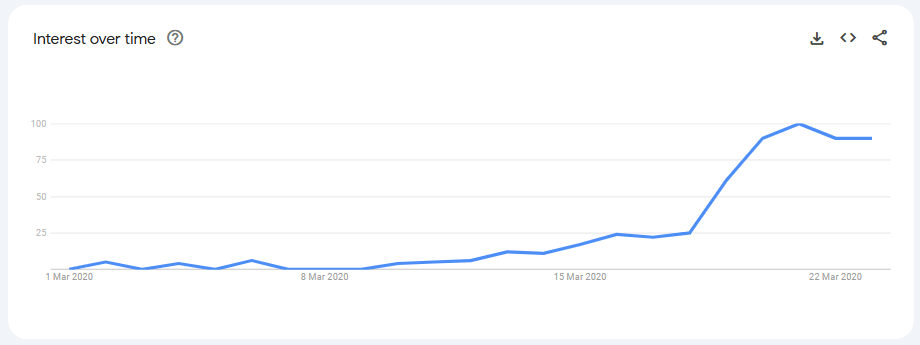

The sixth reason we have for disbelieving the PBS data for hydroxychloroquine in March 2020 is based on our analysis of Google Trends data. From 1 March 2020 to 23 March 2020, web searches for “hydroxychloroquine” only surged from 18 March 2020, again, supporting our contention that Australian interest in hydroxychloroquine commenced around this time. In any event, a simple web search is neither evidence of an intention of, nor opportunity to obtain a hydroxychloroquine prescription. Even if we assumed that Google Trends data actually reflected the intentions of Australians to seek hydroxychloroquine, then these intentions did not emerge until late March. Again, this shows the impossible timeline for nearly double the number of prescriptions to have been issued in March 2020 compared with February 2020:

A seventh reason to disbelieve the March 2020 PBS data for hydroxychloroquine is the obvious inconsistencies in the concerted campaign to discredit the medicine which commenced after Trump’s press conferences. The campaign spanned only a matter of days and combined an open letter from the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA) president Chris Freeman and a follow-up article covering this open letter in the State-sponsored legacy media.

Freeman’s open letter, published Saturday 21 March 2020 (less than one day after Trump’s second press conference), remarkably called for pharmacists to refuse to fill prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine and for prescribers to stop issuing prescriptions for it because of the “unprecedented demand for the drug” at Australian community pharmacies:

“On the background of some promising data showing the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19 and with President Trump’s announcement yesterday, 20 March 2020, that the drug hydroxychloroquine may support the care of patients affected by COVID-19, Australian community pharmacies have seen unprecedented demand for the drug . . .

Our strong advice to pharmacists at this point in time, until further advice is available, is to refuse the dispensing of hydroxychloroquine if there is not a genuine need . . .

PSA would like to keep safe any stock of hydroxychloroquine held in local pharmacies – so it is available to treat patients who genuinely need this medicine. The only way this is possible is for prescribers to not write prescriptions for this medicine as a ‘just in case’ measure and for pharmacists to refuse the supply outside of these indications at this point in time.

While the data may not yet be clear, if hydroxychloroquine is shown to be effective for COVID-19, we want every dose available to treat those who may require it.”7 [emphasis added]

Consider the timeline of events suggested by Freeman in his open letter. Trump’s second press conference had commenced in Washington D.C. at 11:30am EDT (2:30am AEDT). Trump and Fauci’s exchanges with journalists occurred between the 37th and 46th minute of the press conference (3:07am-3:16am AEDT). Following this press conference, it was alleged:

Australian pharmacies faced unprecedented demand for hydroxychloroquine;

They reported this unprecedented demand;

The PSA collated these reports;

The PSA recognised a signal;

Freeman was prompted to write an open letter;

Freeman drafted his open letter; and,

The open letter was published at 1:09pm on the PSA webpage.8

The sequence of events culminating in Freeman’s open letter demonstrates either an unparalleled example of organisational efficiency on behalf of the PSA, or something a little more creative.

There are very good reasons, as we have stated, to doubt that ordinary Australians had paid any attention to the limited but “promising data showing the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19” in scientific studies, and so, Trump’s press conference was the catalyst for this surge in demand for the medicine. But, when Freeman suggested there had been “unprecedented demand” for hydroxychloroquine at Australian pharmacies, he suggested it was Trump’s second press conference, occurring 20 March 2020 in the USA, which caused this surge. Recalling that Trump finished talking about hydroxychloroquine at 3:16am AEDT on Saturday 21 March 2020, only hours before Australians woke up to the news and the open letter was published, it makes the sequence of events proposed in the open letter even more fantastically impossible.

Freeman surely must have been referencing Trump’s statements in the 19 March 2020 press conference that caused this surge in demand, but even then, the opportunity for ordinary Australians to learn about this “news” was limited because of the near-total void of legacy media coverage of the press conference, let alone their limited opportunity to have sought the drug. We conclude, therefore, Australian pharmacies did not experience unprecedented demand for hydroxychloroquine, as claimed in the open letter.

Finally, evidence presented in an Australian study supports our contention that the number of “off-label” prescriptions did not surge in March 2020. Using the same publicly available data from the PBS as we have, combined with an additional dataset consisting of a 10% random sample of all PBS-eligible people provided by Services Australia for analytical use, the study concluded that 78% of the spike in dispensing in March 2020 was among people previously treated with the medicine.9 So, if the PBS data is to be trusted, it was not unprecedented demand caused by “off-label” prescribing of hydroxychloroquine, it was stockpiling among existing users of hydroxychloroquine which caused this surge in demand for the drug. If the conclusions of the study authors are accurate, it would also explain why shortages never actually occurred in April 2020; because the existing supply could be used in the following months by those who had hoarded them in March 2020.

Unpacking the TGA’s decision

Days after the PSA’s open letter was published, Australia’s State media repeated its incredulous claims, embellished with the grievous error that actual shortages of hydroxychloroquine had occurred because of this unprecedented demand.

An Australian Medical Association committee member was quoted in the article as being supportive of restrictions for hydroxychloroquine to avert potential shortages for those with indications for the medicine. In other words, to save the medicine for “those who actually needed them” for “painful flare-ups”, contrasting with those who might have been improperly using it to simply save their lives from lethal COVID-19.10

With consent appropriately manufactured, the TGA announced its decision to restrict which health professionals could prescribe hydroxychloroquine to new patients the very next day on 24 March 2020:

“Initiation of hydroxychloroquine is restricted to the following medical specialties as per the Medical Board list: dermatology; intensive care medicine; paediatrics and child health; physician; and emergency medicine.”11

The logic of the TGA’s intervention was an obvious false dichotomy. On the one hand, we had a devastating virus sweeping the globe threatening to wipe out entire populations and a specific medicine was showing hope it could end COVID-19. But on the other hand, we needed to preserve precious supplies of this medicine to provide relief to those suffering the symptoms of lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.

Could we really only supply medicine to one group or the other?

No.

Shortages are not only overcome by trying to curtail demand (through regulations or increased prices) but also by increasing supply. If shortages were honestly the concern, then these could have easily been alleviated by sourcing hydroxychloroquine from one of the many global producers.

Supply could have also been secured through investments in manufacturing hydroxychloroquine domestically. The original patents for hydroxychloroquine had long since expired, making it available as a generic and low-cost medication. Its synthesis involves well-known chemical processes, and the raw materials are generally accessible. Many countries, even those with developing pharmaceutical industries, have the capacity to manufacture hydroxychloroquine at scale.

Yet, we picked mRNA.

Though shortages of essential medicines could be concerning, (and even after the TGA restrictions were imposed, hydroxychloroquine shortages occurred twice in 2020) these should have been easily managed by an advanced industrialised economy with a properly functioning pharmaceutical procurement system.

However, a brief four-day period of heightened media attention and so-called “recent reports” were sufficient to prompt the TGA’s intervention:

“Recent reports of increased off-label prescribing of medicines containing hydroxychloroquine have raised concerns that this will create a potential shortage of this product in Australia.”12 [emphasis added]

The “recent reports” were the only evidence cited by the TGA in its decision and it failed to provide the source(s) for these “reports” in yet another example from the recent past of its opaque decision-making, which we have regrettably come to expect from the organisation.

So, who kept using hydroxychloroquine in 2020, causing the shortages?

Two shortages for hydroxychloroquine occurred between late August and early October 2020.

The exact nature of the first shortage was unknown, but the second was caused by “unexpected consumer demand”, which we presume to mean Australian consumers.

Curiously, however, the PBS data, revealed a consistent pattern of prescribing hydroxychloroquine during this time (highlighted in red below) suggesting that the use of hydroxychloroquine had increased even though the number of prescriptions had not:

So, what could have driven the “unexpected consumer demand” to have caused at least one of these shortages?

One possible answer was its increased use in clinical trials. But, there were limited clinical trials being conducted at the time, with the exception of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne. Its August 2020 COVID Shield Clinical Trial was reported to have planned the recruitment of only 650 participants: not enough to have caused the reported shortage. Prior to the COVID Shield Trial, many other clinical trials had removed hydroxychloroquine from its multi-drug trials too. The increased use was not, therefore, caused by large clinical trials sapping the supply of hydroxychloroquine.

The second, more plausible answer, is that hydroxychloroquine was being used in hospitals “unexpectedly”. Both public and private hospitals’ inpatient treatment is funded by the hospital or state health budgets, not the PBS, and so, these supplies do not appear in PBS statistics which could explain why the prescriptions had remained within expected bounds in the second half of 2020. The TGA intervention, as restrictive as it was, still allowed for “initiation of hydroxychloroquine” in “intensive care, paediatrics and child health, physician and emergency medicine”, meaning that the clinical judgement of doctors in hospitals was still respected and hydroxychloroquine could be prescribed freely: even for COVID-19 in Australian hospitals.13

Throughout 2020, Australia’s Federal Government continued to stockpile hydroxychloroquine, waiving regulatory requirements for the importation and supply of the drug. It was reported at the time that doctors never ceased providing it to COVID-19 patients in hospital too.

But, why would doctors in hospitals be using more hydroxychloroquine in late August 2020 to have caused these shortages?

It surely had everything to do with Australia’s second COVID-19 wave commencing in July 2020.

As shown above, during the second wave beginning in July 2020, both COVID-19 hospitalisations and ICU admissions climbed steadily, with ventilated patients remaining a subset of those in ICU. Although these categories peaked in July and early August, they later decreased, suggesting many individuals were discharged or recovered. Throughout both waves, the data demonstrate that a sizeable fraction of hospitalised individuals did not progress to ICU care, and only a portion of ICU patients required mechanical ventilation.

Remember, all of these “COVID-19 hospitalised” and “COVID-19 ICU-admitted” and “COVID-19 ventilated” patients presenting to hospital (about 12.5% of all “COVID-19 Cases” in 2020 in Australia) were all “unvaccinated” too.

Something was responsible for these recoveries, and it was all before the arrival of the miracle “vaccines”.

Could these outcomes have been, at least in part, driven by the unexpected surge in hydroxychloroquine demand?

There are two other strange coincidences in the data which support this hypothesis. First, the start of the downward trajectory in the number of “COVID-19 hospitalisations” occurred almost exactly to the day that the first hydroxychloroquine shortages were reported in the TGA’s database, perhaps providing a clue that the available hydroxychloroquine stock was used up to treat these patients. Second, the “supply impact end date”, for the resolution of the “unexpected consumer demand” coincided with the return to “normal” “COVID-19 hospitalisation” numbers, suggesting that hydroxychloroquine stocks were predicted to be replenished once the “unexpected” overuse in hospitals had ceased.

Australia’s record with “COVID-19 deaths” also shows how the standard of care provided in Australian hospitals was highly effective in 2020. In 2020, Australia recorded only 909 “COVID-19 deaths”, most of which, however, occurred in Residential Aged-Care Facilities (RACFs), where the standard of care in many facilities was inhumane.14 678 of Australia’s 909 “COVID-19 deaths” in 2020 occurred in RACFs, and so, even if we assume that the entirety of these remaining 231 deaths occurred in hospital, from the nearly 30,000 “COVID-19 cases” in 2020, the Case-Fatality Rate (CFR) for “COVID-19” patients (not RACF patients) was still less than 1%; only slightly higher than the CFR for seasonal influenza.15

Conclusion

Our article reveals how the TGA’s decision to restrict the supply of hydroxychloroquine was neither a measured response to safety concerns nor a necessity driven by genuine shortages. Instead, it was a capitulation to the interests of its pharmaceutical sponsors who had no financial stake in an inexpensive, off-patent drug like hydroxychloroquine, but a much larger financial stake in the development of new “vaccines”.

In 2020, there was a continued supply of hydroxychloroquine to those hospitalised with COVID-19 and the evidence shows that in 2020, Australian doctors had developed a standard of care which, on two occasions, had “flattened the curve” in Australian hospitals and, remarkably, resulting in the near complete elimination of “COVID-19 cases” in the community.

We know that hydroxychloroquine continued to be used as a treatment for those hospitalised with COVID-19 to the extent that it caused at least one shortage for the medicine in 2020 and, despite likely fraudulent anomalies in DAEN, there were no safety signals for hydroxychloroquine in 2020 despite this increased use.

Yet, somehow, within a matter of days starting in late March 2020, hydroxychloroquine went from the “game-changer” to the drug which could kill indiscriminately from all manner of horrible side-effects.

These events show how swiftly and in unison the Bio-Pharmaceutical Industrial Complex can pull its many levers to influence governments and regulators, co-opting legacy and State media mouthpieces to shape medical policies and public perception about a once “Essential Medicine”.

For the uninitiated, the origin of the term derives from the “Military-Industrial Complex” warning given by American President Dwight D. Eisenhower in his farewell address to the nation on January 17, 1961. Here is the key excerpt from his speech:

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The 1 potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

Eisenhower warned that the close relationship between the military and the defense industry could lead to excessive military spending and a diversion of resources from other important areas. He urged citizens to be vigilant and to hold their government accountable to prevent the military-industrial complex from gaining too much power.

The language “off label use” also appears in different ways in the data: “product use in unapproved indication” and “intentional product use issue”.

It would appear that the term “significant” for the “adverse events” noted by the TGA in its 24 March 2020 press release was used quite loosely. As one example, blurred vision, whilst undesirable, is not really comparable with cardiomyopathy in severity.

Li, R., Curtis, K., Zaidi, S. T. R., Van, C., Thomson, A., and Castelino, R., “Prevalence, Characteristics, and Reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions in an Australian Hospital: A Retrospective Review of Hospital Admissions Due to Adverse Drug Reactions”, Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 2021, 20(10), 1267–1274. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2021.1938539

Reports of shortages in the TGA database occur for one of only seven reasons, and these results from December 2014 to August 2024 show the frequency of these occurring:

Manufacturing (3,842 times)

Unexpected increase in consumer demand (1,215 times)

Commercial Changes / Commercial viability (1,036 times)

Other (1,090 times)

Transport / Logistic issues / Storage capacity issues (360 times)

Product recall (46 times)

Seasonal depletion of stock (13 times)

We acknowledge that heightened fear in the community could have led to people believing the opposite effect was true. Heightened fear in the community might make people more likely to present to their GPs seeking a “cure”. But, we think this was less likely for many reasons. First, it was very early in Australia’s first COVID-19 wave and the fear of COVID-19 was still in its infancy in the community, despite the best efforts of the State and legacy media to drum up fear. Second, GPs were tightening their requirements for face-to-face consultations meaning that they would have restricted access to people demonstrating even the slightest of any of the catch-all COVID-19 symptoms. Third, people might have been fearful of going to the doctor where other sick people were also going; possibly with the dreaded COVID-19. Fourth, even if people were feeling sick enough to go to the doctor, “doing the right thing” was staying at home and managing your symptoms, whatever they were, at home.

PSA, “Prescribing Hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19”, https://www.psa.org.au/prescribing-hydroxychloroquine-for-covid-19/, (archive link), accessed 13 January 2025.

The time of publication was verified in the webpage’s source code.

Schaffer A.L., Henry D., Zoega H., Elliott J.H. and Pearson S.A., “Changes in Dispensing of Medicines Proposed for Re-Purposing in the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia”, PLOS ONE, 17(6): e0269482, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269482, p. 6.

Sydney Morning Herald, “Malaria and Arthritis Drugs Touted as Potential Coronavirus 'Cure', Triggering Pharmacy Rush”, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-23/malaria-drugs-labelled-early-coronavirus-covid19-cures-treatment/12081306, (archive link), accessed 14 January 2025.

TGA, “New Restrictions on Prescribing Hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19”, https://www.tga.gov.au/news/safety-alerts/new-restrictions-prescribing-hydroxychloroquine-covid-19 (archive link), accessed 11 January 2025.

Ibid.

Ibid.

In all of our articles, when we write “COVID-19 deaths” and “COVID-19 cases” we have intentionally placed these terms in inverted commas to emphasise their ambiguity and the potential for them to be misleading. There are very good reasons to distrust the accuracy of PCR-testing. We have previously addressed the dodgy data from PCR-testing methodology. See here: https://www.shiftedparadigms.org/i/137653276/the-world-health-organisation-who-guidance or for more expert commentary read the excellent “Where are the Numbers” Substack.

For “COVID-19 deaths” data, see:

Department of Health, “COVID-19 outbreaks in Australian residential aged care facilities”, https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/12/covid-19-outbreaks-in-australian-residential-aged-care-facilities-30-december-2020-covid-19-outbreaks-in-australian-residential-aged-care-facilities-30-december-2020.pdf, archive link, p. 1, accessed 5 January 2024.

Many “COVID-19 deaths” have occurred at home but the precise number is difficult to find. See here: https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/most-health-departments-not-tracking-covid-home-de

In all likelihood, COVID-19’s CFR was much smaller than this and has always appeared higher because of pandemic surveillance methodologies which count all incidental deaths with COVID-19 as “COVID-19 deaths”.

Brilliant work - thank you so much. It is a very thoroughly researched and well-written investigation.

Rising awareness of all the facets of this colossal abuse of power that costs lives and eats up our hard-earned dollars is one thing we can do. Keeping the bright spotlight of awareness and truth directed at these dark people and methods will eventually flush the cockroaches out because they can only hide in the dark. Keep it up.

Quoting:

The TGA’s “…intervention undermined trust in medical professionals, disrupting the doctor-patient relationship and denying a proven safe and effective early treatment for COVID-19 to Australians”.

Absolutely correct!

The public officials in charge of the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) played a key role in enabling the public health disaster that the experimental mRNA genetic injectables have inflicted – (and continue to inflict) - on the health of Australian people.

More than at any other time in Australian history, there is a compelling need for an inquisitorial tribunal with the powers of compulsion to investigate these TGA officials to discover who exactly decided to ban the use of Hydroxychloroquine, how the TGA’s subsequent grant of ‘provisional’ approval to the novel mRNA genetic technology was made, when those decisions were made, and in particular, WHY? Something really stinks about the whole thing – and that stink really comes to the fore when you watch the TGA and other public ‘health’ officials later being subjected to interrogation by senators in the Australian senate hearings. It was embarrassing to watch these public officials duck and weave to avoid answering the Senators questions.

Any inquiry needs to have the power to examine the bank accounts and assets of the TGA officials and those of their relatives, as well as the accounts of their ‘customers’ – the pharmaceutical corporations. One byproduct of the actions of the TGA public officials is that they have brought into extreme disrepute the whole Australian Government public service.

And then there is the matter of the role of the politically incompetent Prime Minister Morrison and his former Health Minister – the latter having once been a managerial employee of the World Economic Forum before he entered politics to commence his meteoric rise. There really is a very bad smell about the whole thing. All these people need to be compelled to answer questions about why the rate of ‘vaccine’ injury from the mRNA genetic injectables is so high, and why the rate of “all-causes” mortality in Australia following the mRNA injection campaign has soared. None of these people should ever be let off the hook – justice and the bereaved families demand it.