From the onset of the pandemic, all interventions promoted and mandated in Australia were concerned with protecting the most vulnerable to COVID-19 induced severe illness and death.

Who were these most vulnerable?

Despite the fear and panic that COVID-19 was a disease that could strike the young, healthy and especially the unvaccinated with particular severity, the early empirical evidence seemed to suggest that the people most at risk from COVID-19, were the aged, comorbid or the immunocompromised.

Together, these groups were evidently the most vulnerable to the disease and, to an objective observer at least, very little has changed in that reckoning today.

So, how did we do protecting these groups?

Mortality in excess from the “baseline average”

To calculate recent excess mortality in Australia, the ABS uses two “baseline averages” to establish “expected deaths”:

For the year 2022, only the years 2017-2019 and 2021 are included; and,

For the year 2021, the years 2015-19 are included.

So, the baseline average for 2022 comprises only four years, compared with five for the baseline average for 2021.

The year 2020 is not included because, as the ABS affirms, it was a particularly low-death year which could, if included in the baseline calculation, “artificially indicate higher than expected mortality in the years following”.1

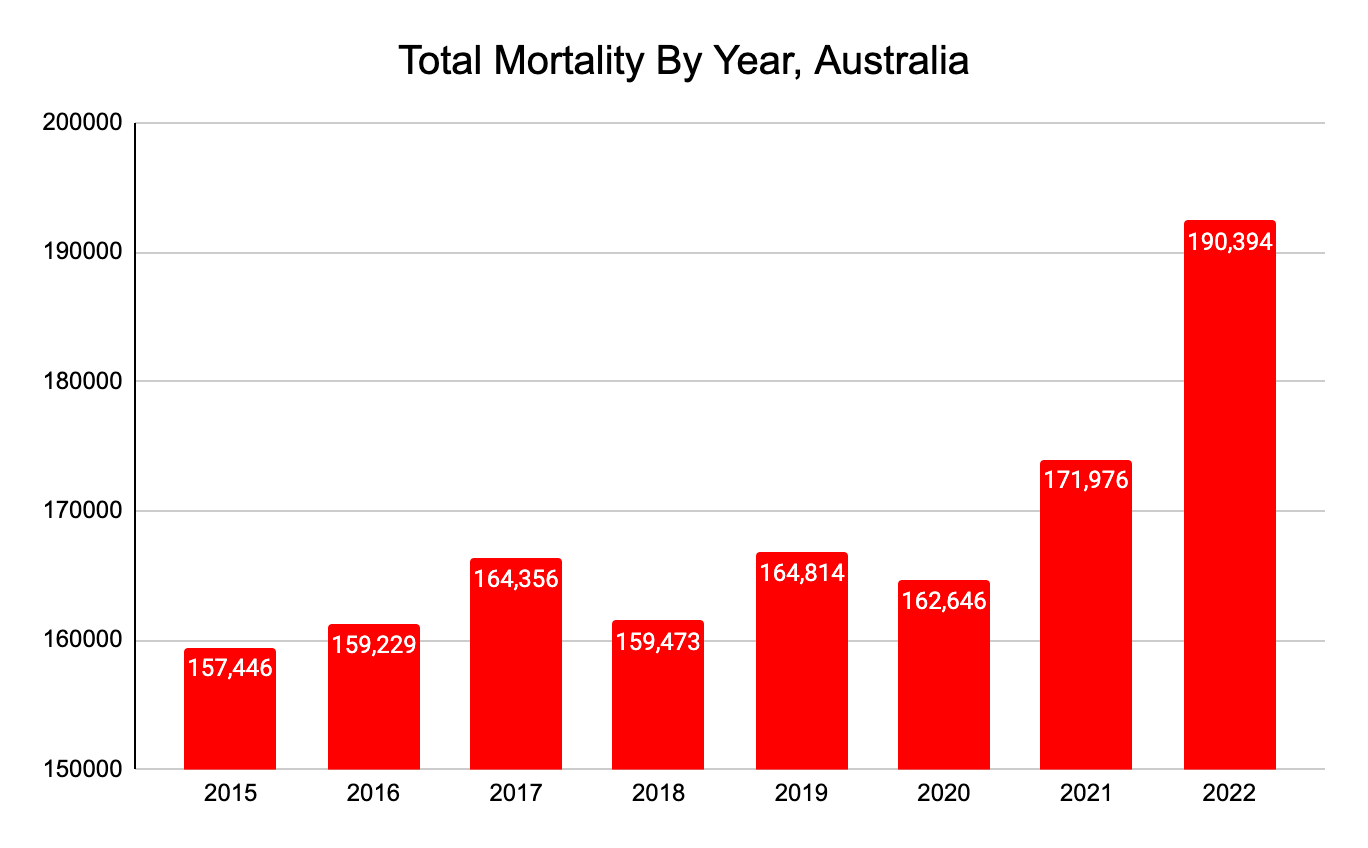

Strange then that the year 2018 was not excluded from the baseline average in the ABS methodology, given it was a similarly low-death year:

Nevertheless, for the purposes of simplicity, let’s accept the ABS’s methodology which excludes the year 2020, which if included, would make excess mortality for 2022 seem significantly worse than it was.

The impact of COVID-19 stratified by age and sex

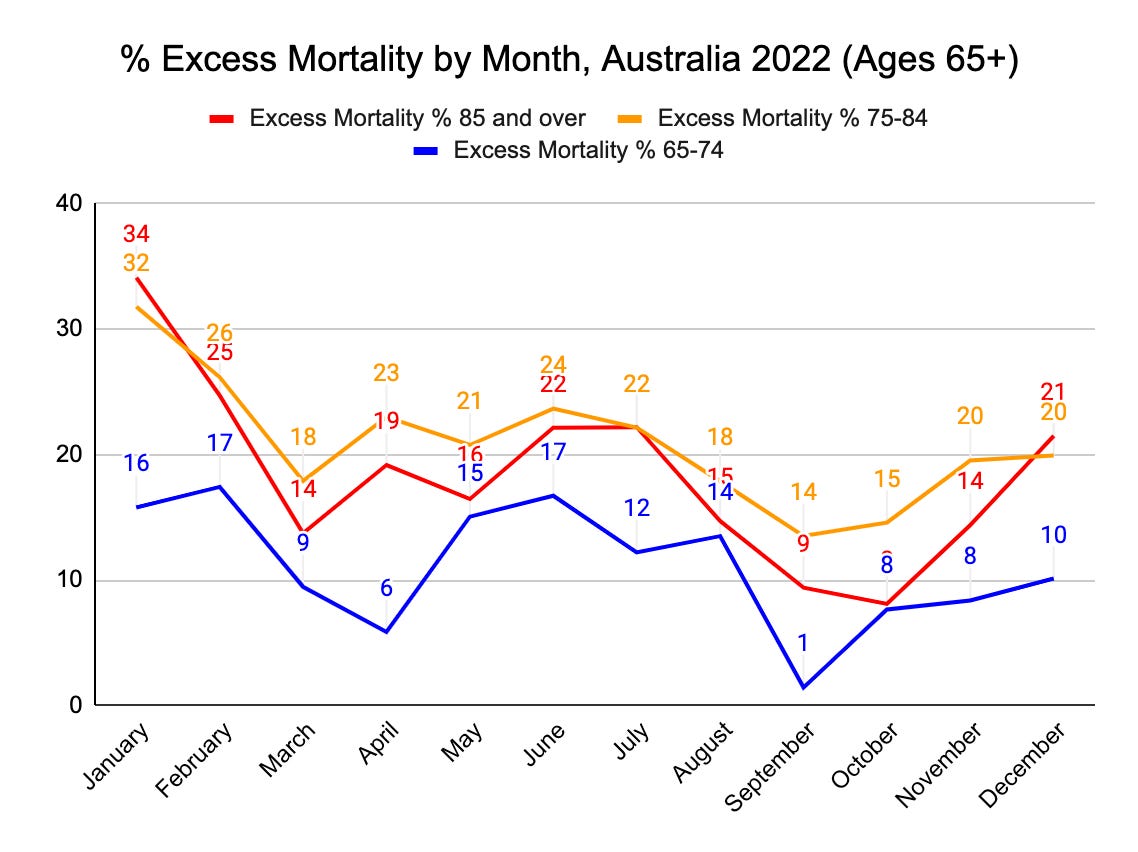

The 15.4% excess mortality for all-ages in Australia in 2022 masks significant excess mortality in all the 65 years and over age brackets.

These 2022 mortality data, when stratified by age, are horrific:

85 and over - 12,133 excess deaths

75-84 - 8,820 excess deaths

65-74 - 2,935 excess deaths

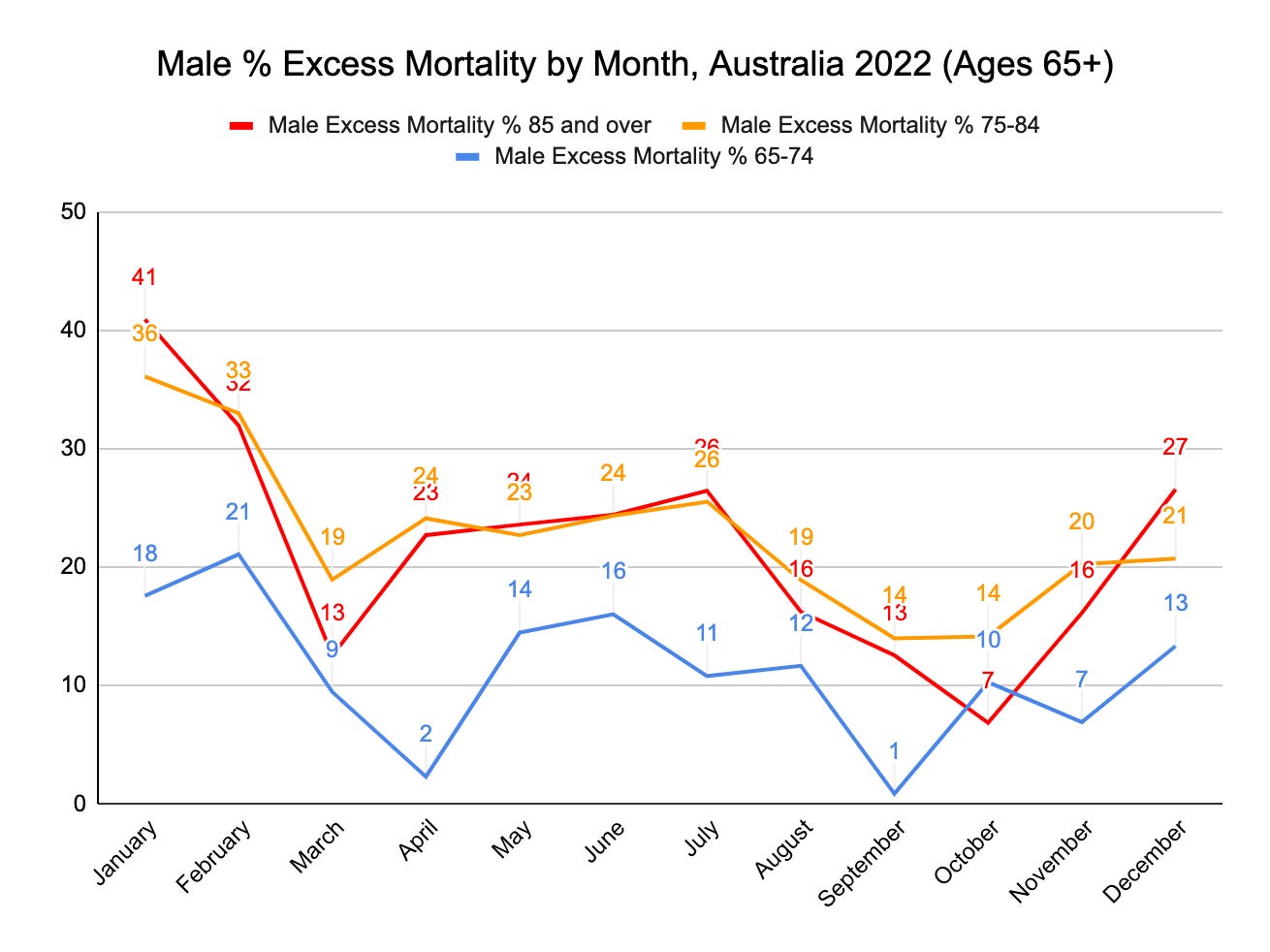

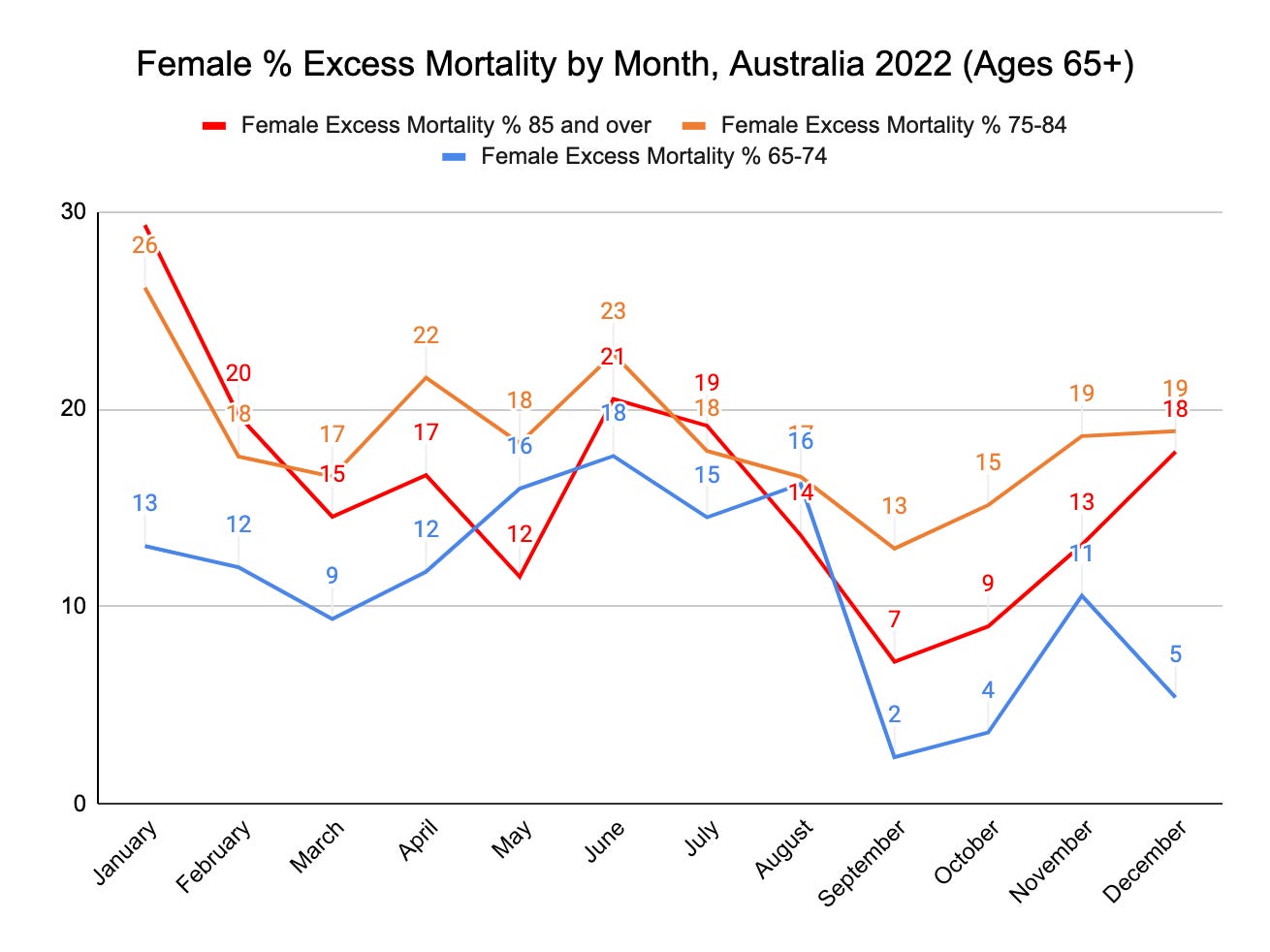

The excess mortality in the 65 and over demographic are particularly worse for males compared with females:

January 2022:

41% excess deaths for males aged 85 and over

36% excess deaths for males aged 75-84

February 2022:

32% excess deaths for males aged 85 and over

33% excess deaths for males aged 75-84

21% excess deaths for males aged 65-74

July 2022:

26% excess deaths for males aged 85 and over

26% excess deaths for males aged 75-84

December 2022:

27 % excess deaths for males aged 85 and over

21% excess deaths for males aged 75-84.

The concerning omission in these data is the deaths which occurred in 2022 which have not yet been registered and will be added to future reports.2

During this period of exceptional excess mortality in Australia, one should expect that these dire numbers will likely only worsen as time goes on and further revisions are made.

The outcome for aged people in Australia in 2022, therefore, could only accurately be described as extremely poor.

What else does the ABS “Provisional Mortality” data reveal?

To determine the nature of Australia's excess mortality, the only dataset available at present is the "Provisional Mortality Statistics" release, and the data is "preliminary and subject to change".3

What we "provisionally" know, however, is that in 2022 in Australia, there were:

190,394 total deaths, 167,457 of which have been been doctor-certified and a cause of death is stated;

134,110 of these doctor-certified deaths were the result of a “leading cause of death” (such as diabetes, dementia, cancer, COVID-19 to name a few);

33,347 deaths are “uncategorised” (not resulting from a “leading cause”) as reported in this release;

22,937 deaths have "unknown" causes because either:

They have not yet been doctor-certified because of time lags in death registration; or,

A coronial investigation is ongoing.4

Potentially, in a year of exceptional excess mortality, there may be many deaths that are under investigation by the coroner’s courts in Australia because deaths are referred to the coroner (among other reasons) if:

The death is sudden and the cause of it unknown [emphasis added];

The death occurred during or following a health-related procedure where the death is or may be causally related to the procedure and a registered medical practitioner would not, immediately before the procedure was undertaken, have reasonably expected the death [emphasis added]; and/or,

Medical Certificate of Cause of Death has not been signed and is not likely to be signed (for example, where an opinion about the probable cause of death cannot be formed).5

It is expected, therefore, that coroner-referred deaths might account for many of these uncategorised deaths for the following reasons.

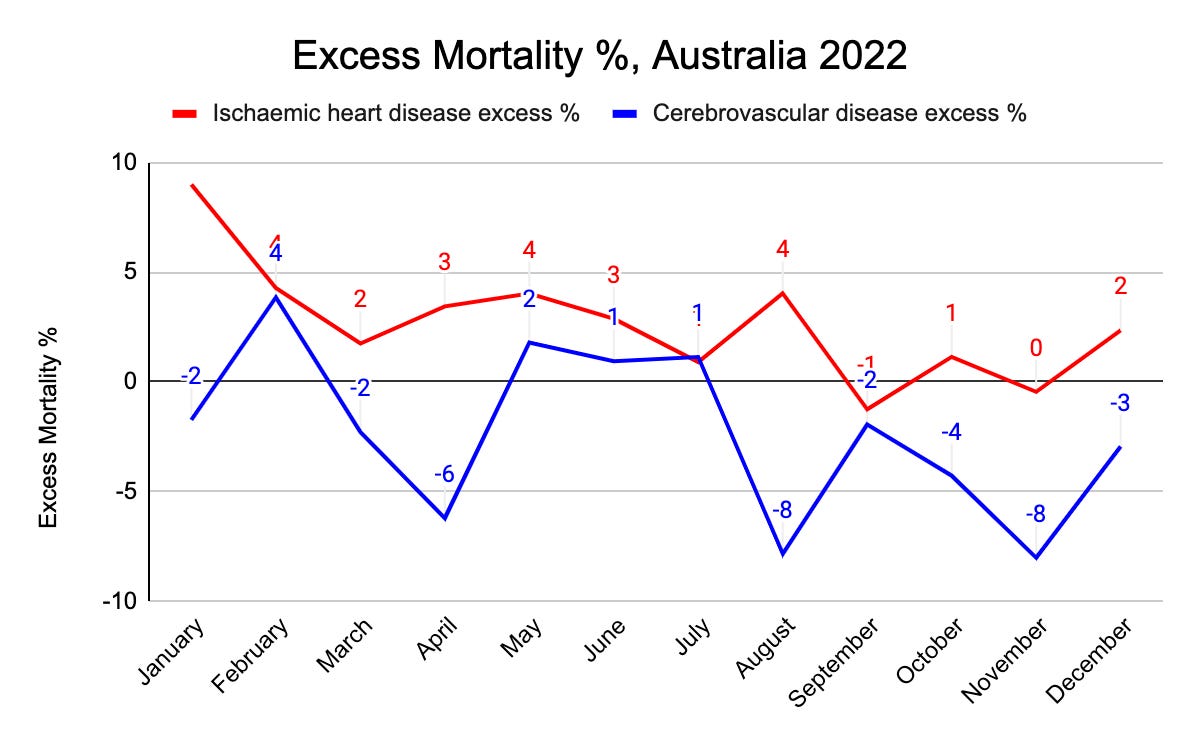

First, it could be presumed that conditions like ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease have higher coroner referral rates because they are conditions which might more commonly cause "sudden death" than other causes, and therefore, require a coronial investigation.6

Second, ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease can also lead to the development of other health problems, such as heart attacks, cardiac arrest, myopericaditis, stroke or thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome; all of which correspond with some of the most well-known serious adverse events following COVID-19 vaccination. If these deaths occurred following a “health-related procedure”, even if it only may have been causally related, it would require a coronial investigation. So, if a temporal association between COVID-19 vaccination (a health-related procedure) and a death exists, then doctors and healthcare professionals are statutorily obligated to report deaths to the coroner even if there is the possibility that a “health-related procedure” only may be causally related to the death.7 Certainly, the observational evidence showing an increase in the sudden deaths of otherwise seemingly fit and healthy adults could be creating a surge in coroner-referred cases which is delaying registrations of death and the release of more fulsome data from the ABS.

Third, one might assume that doctors and healthcare professionals may be unwilling to state a probable cause of death that might breach their restrictive and censorial professional guidelines, and so, refer these deaths with “unknown causes” to the coroner.8

So, although at the present moment, the contribution of ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths to excess mortality in 2022 appears understated, these data will likely change as currently open coronial investigations are completed and reported on in subsequent ABS “Causes of Death” releases ongoing:

Complicating the mortality figures further, are the likely delays to the “Causes of Death” reporting by the ABS. We do not yet have the complete picture of even the 2021 deaths data, when the number of deaths were significantly lower, and presumably there were far fewer coroner-referred deaths. The ABS "Causes of Death, Australia, 2021" release describes how many coronial investigations had not been completed by the time the 2021 data was coded. As a result, there were many deaths listed as “other ill-defined and unspecified causes of mortality” or "ill-defined and unknown causes of mortality". There are still 4,763 deaths from 2021 to be explained.9 It is anticipated that the soaring excess mortality in 2022 will contribute to delays in death registrations, coronial investigations and, therefore, our understanding of the true nature of the exceptional excess mortality in 2022.

Why did so many people die in 2022?

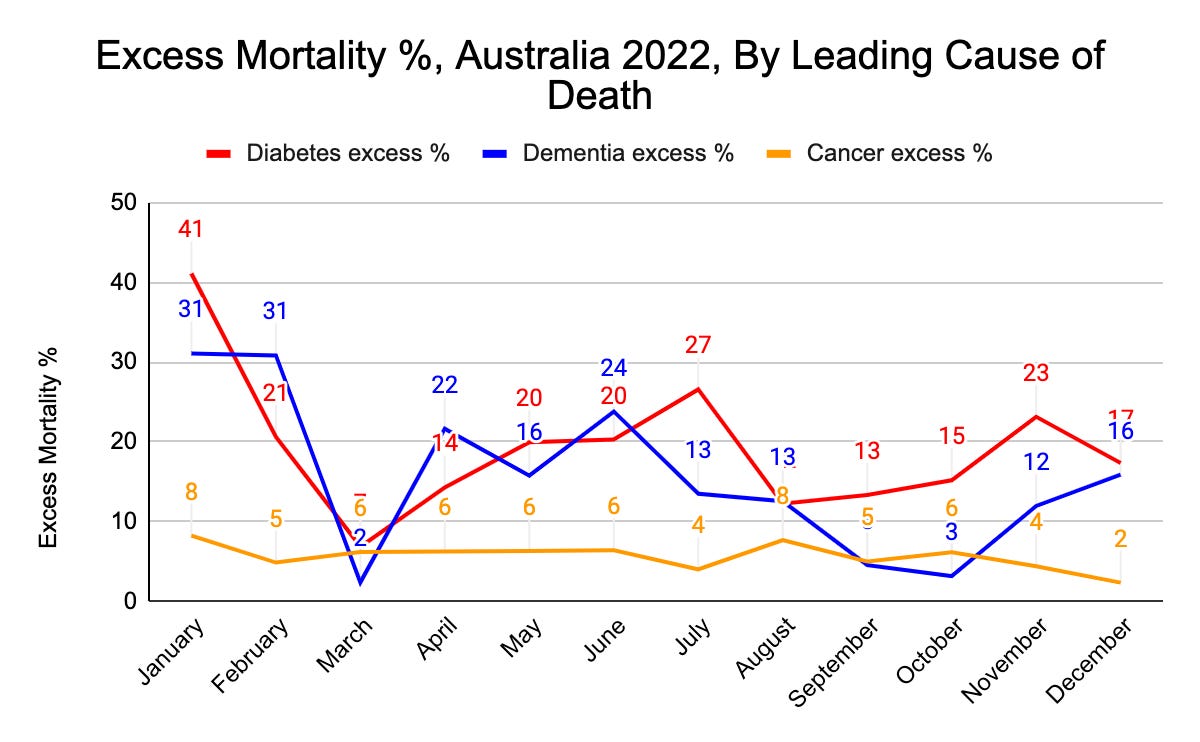

Though the data is “preliminary and subject to change”, the Provisional Mortality Statistics provide insights into what had contributed significantly to the excess mortality, with the top three of the leading causes shown:

Once again, staggering death statistics are evident in 2022:

41% excess diabetes deaths in January

31% excess dementia deaths in January-February

27% diabetes excess deaths in July

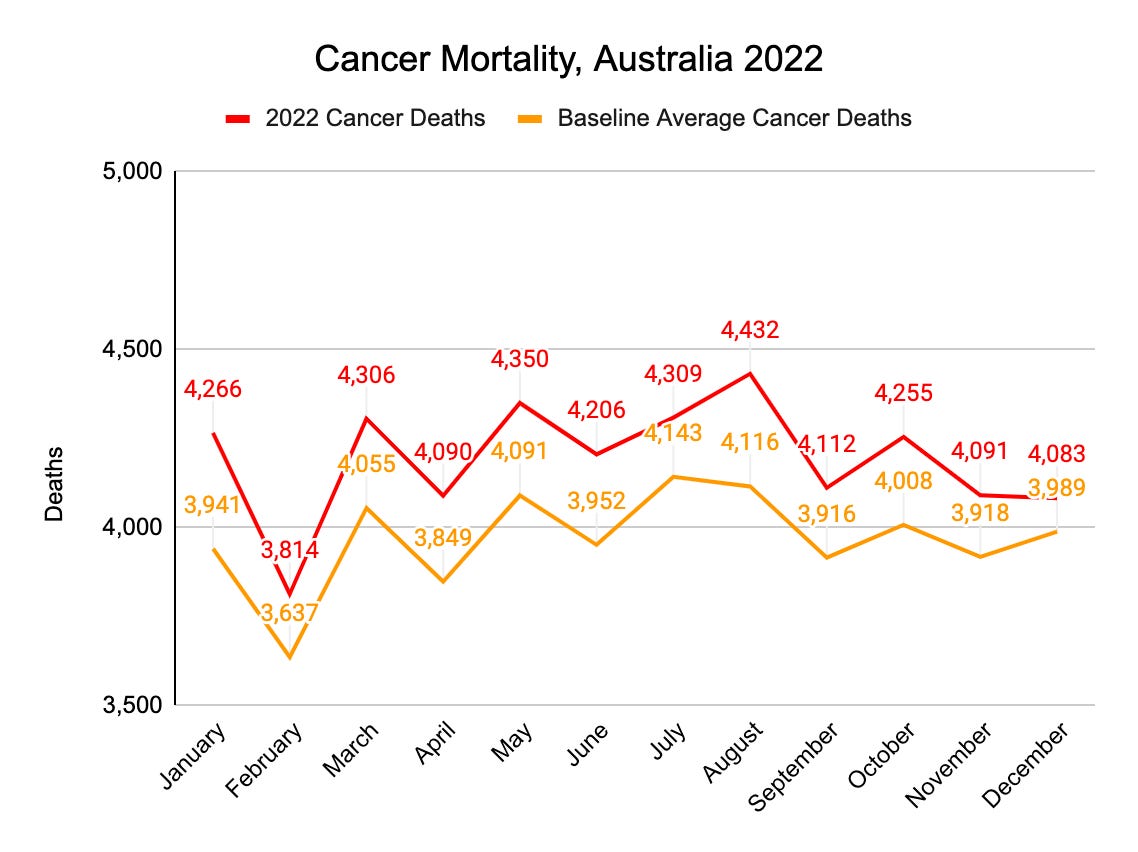

Although displaying cancer deaths as percentage deviations from the baseline average can make them appear less significant than they actually were, it should be noted that this was not the case in 2022. Cancer deaths totalled 50,314, an increase of 2,699 cancer deaths, or, an increase of 6% from the cancer deaths baseline average:

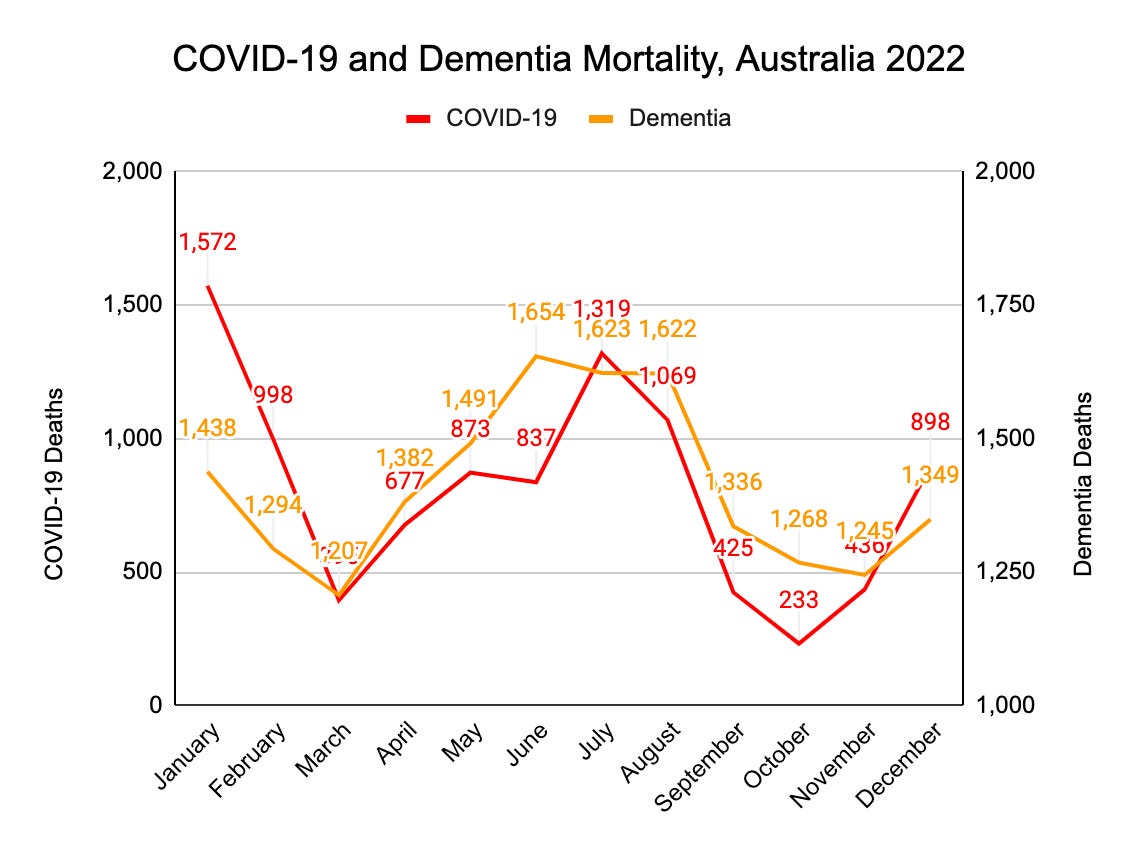

Similarly, dementia deaths increased to 16,909 deaths in 2022; an increase of 2,230 deaths from the dementia deaths baseline average.

So, Australian excess mortality soared in 2022: particularly so for aged, comorbid and immunocompromised people.

In other words, excess mortality soared in the most vulnerable groups we were most intent on protecting.

So, the outcome for comorbid or immunocompromised people in Australia in 2022, therefore, could only accurately be described as also extremely poor.

Further questions

So, just who were these miracle vaccines protecting?

What net benefits, if any at all, did all public health interventions provide?

Though it is beyond the scope of this post to delve more deeply into the causes of excess deaths in diabetes, dementia and cancer (among others in the leading causes of death), it should be noted that these diseases do not cause sudden deaths by comparison with ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, and will have, undoubtedly, taken longer to materialise.

Lockdowns are likely a significant contributing factor to the excess deaths. Lockdowns created disruptions to medical treatments, exacerbated existing inequalities with access to health services, caused significant economic disruption, and reduced the populations’ physical activity among many other egregious effects from this calamitous public “health” policy.

In Australia, aged-care homes (where dementia patients predominantly reside) have been operating under pseudo-lockdowns since the start of the pandemic. So, the argument that lockdown policies have contributed to the rise in dementia deaths does not sufficiently explain the monthly fluctuations in dementia deaths throughout 2022. If lockdown policies were solely to blame for increases in dementia deaths, then we might expect dementia deaths to be less variable through the year.

What do we observe instead?

Deaths from dementia directly vary with COVID-19 deaths:

Given that the severest restrictions have existed in aged-care homes for such a long time, the pattern of dementia deaths is curious.

Is it possible that COVID-19 deaths of dementia patients could have been misclassified as “dementia deaths” rather than “COVID-19 deaths”?

If so, this could make the COVID-19 vaccines seem safer and more effective than they actually are.

What if those dementia deaths were actually caused by adverse reactions to COVID-19 vaccination?10 If so, it might provide one explanation for the monthly variations in dementia observed in 2022. After all, why should a dementia patient be more suspectible to die of dementia during a surge in COVID-19 cases in the general community?

Would an excess 2,230 deaths for 2022 look better as dementia deaths or COVID-19 deaths?

It would depend on the narrative.

On the one hand, patients with dementia are expected to die of dementia in aged-care homes: no further questions, no public inquiries, no royal commissions.

On the other hand, if excess mortality not seen since World War Two in Australia has resulted from the use of a biotechnology therapeutic to treat a novel coronavirus: we are in Nuremberg Trials territory.

Let’s safely assume that it would it would not be unreasonable to believe that the vaccine propagandists would prefer us to believe the narrative that Australia is experiencing a crisis in mortality from other leading causes: not from COVID-19 or COVID-19 vaccines.

A thought experiment to conclude

These are speculative questions only and in the absence of more fulsome data at this point in time, we are left with a less than complete picture of the nature of Australia’s excess mortality.

In place of the complete picture and explanation, let’s consider the highly simplified thought experiment involving four separate propositions.

Proposition # 1: The COVID-19 vaccines are both safe and effective. Therefore, the COVID mortality rate and the non-COVID mortality rate should be expected to decrease. There is no excess mortality.

Proposition # 2: The COVID-19 vaccines are unsafe but effective. Therefore, the COVID mortality rate should decrease, however, the non-COVID mortality rate should increase. There is excess mortality, but is not comprised, in any large way, of COVID-19 deaths.

Proposition # 3: The COVID-19 vaccines are safe but ineffective. Therefore, the COVID mortality rate should increase, however, the non-COVID mortality rate should not increase. There is excess mortality and it is mainly comprised of COVID-19 deaths.

Proposition # 4: The COVID-19 vaccines are neither safe nor effective. As a result, the COVID mortality rate and the non-COVID mortality rate should increase. There is excess mortality comprising both COVID and non-COVID deaths.

As Australia’s experience in 2022 undoubtedly resembles Proposition # 4, we might conclude, at least in the interim, that the COVID-19 vaccines are neither safe nor effective.

The burden of proof now lies with those who argue that the COVID-19 vaccines contributed significantly to mitigating the impact of the pandemic, and that the situation would have been much worse without them: that is, even worse excess mortality than we saw in 2022 without the miracle vaccines and curve-flattening lockdowns.

Excess mortality is an endpoint with which we can evaluate the risk-benefit equation of all pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions during the pandemic years. As the combined mortality for the most vulnerable in Australia was so significantly beyond expectation in 2022, we can conclude that, at this point in time, the risks of the preventative measures taken against COVID-19 have outweighed the benefits.

Accordingly, an urgent review of the safety and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines, and of the non-pharmaceutical interventions is needed.

The Paradigm is shifting.

ABS Provisional Mortality Statistics, Jan-Dec 2022 Methodology, accessed 21 April 2023

ABS Provisional Mortality Statistics, Jan-Dec 2022, accessed 17 April 2023

Provisional Mortality Statistics, Jan-Dec 2022 Methodology, accessed 21 April 2023

Preliminary data outlining some of the major causes of death are provided in the Provisional Mortality release, but is subject to change. The “Causes of Death” for 2021 was not released until October 2022, and so, the earliest one might expect the “Causes of Death” series for 2022 might be around the same time, although the ABS lists the release date as “unknown”. ABS Provisional Mortality Statistics, Jan-Dec 2022, accessed 17 April 2023

Coroners Court of NSW, “When a death must be referred to the coroner”, link, accessed 21 April 2023

ABS Provisional Mortality Statistics, Jan-Dec 2022, accessed 21 April 2023

Coroners Court of NSW, “When a death must be referred to the coroner”, link, accessed 21 April 2023

“‘Ask AHPRA’: Dr Kerryn Phelps doesn’t know why regulator silenced doctors on vaccine injuries”, https://www.news.com.au/technology/science/human-body/ask-ahpra-dr-kerryn-phelps-doesnt-know-why-regulator-silenced-doctors-on-vaccine-injuries/news-story/a731a655120649f913c8170bfbf1bb96, accessed 21 April 2023, (archive link here)

ABS Causes of Death, Australia, 2021, accessed 21 April 2023

http://www.aginganddisease.org/EN/10.14336/AD.2021.1102

It's clear from the age-stratified statistics that the excess is in the 65+ (esp. 75+) cohorts. They even show increases every booster campaign (see Graph 3):

https://fullbroadside.substack.com/p/sustained-overkill

A workmate who is enduring guardian of his "care"-homed mother told me they push every booster on all residents. They threatened to expell his mum from her care home unless she got "up-to-date" on her booster regimen. This was *this week*, Apr.24, 2024. He has so far refused to comply.